By Charles Boccadoro

FundX Upgrader Fund(FUNDX) is now FundX ETF(XCOR) – January 24, 2023

Objective and Strategy

The FUNDX Upgrader Fund seeks to maximize capital appreciation. It is a fund of active or passive funds and ETFs. 70% of the portfolio is in “core funds” which pursue mainstream investments (e.g., Oakmark Global OAKGX), 30% are more aggressive and concentrated funds (e.g., Wasatch Intl Growth WAIGX and SPDR S&P Homebuilders XHB). FUNDX employs an “Upgrading” strategy in which it buys market leaders of the last several months and sells laggards. The fund seems to get a lot of press about “chasing winners,” which at one level it does. But more perhaps accurately, it methodically attempts to capitalize on trends within the market and not be left on the sidelines holding, for example, an all-domestic portfolio when international is experiencing sustained gains.

The advisor’s motto: “We’re active, flexible, and strategic because markets CHANGE.”

Advisor

FundX Investment Group (formerly DAL Investment Company, named after its founder’s children, Douglas and Linda) is the investment advisor, based in San Francisco. It has been providing investment advisory services to individual and institutional investors since 1969. Today, it invests in and provides advice on mutual fund performance through individual accounts, its family of eight upgrader funds, and publication of the NoLoad FundX newsletter.

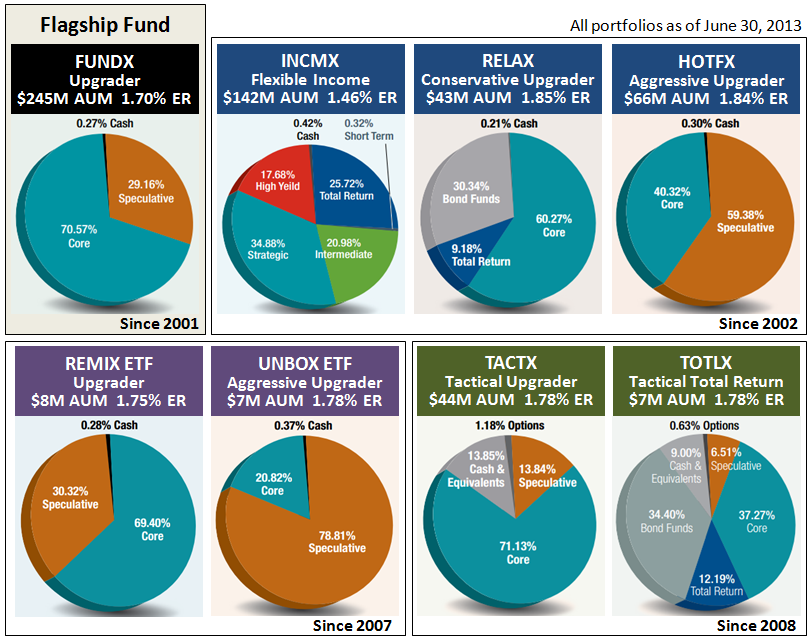

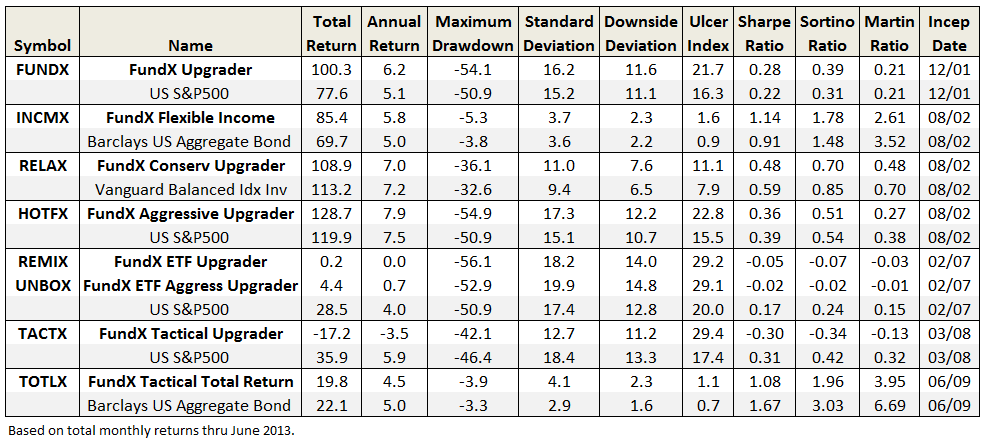

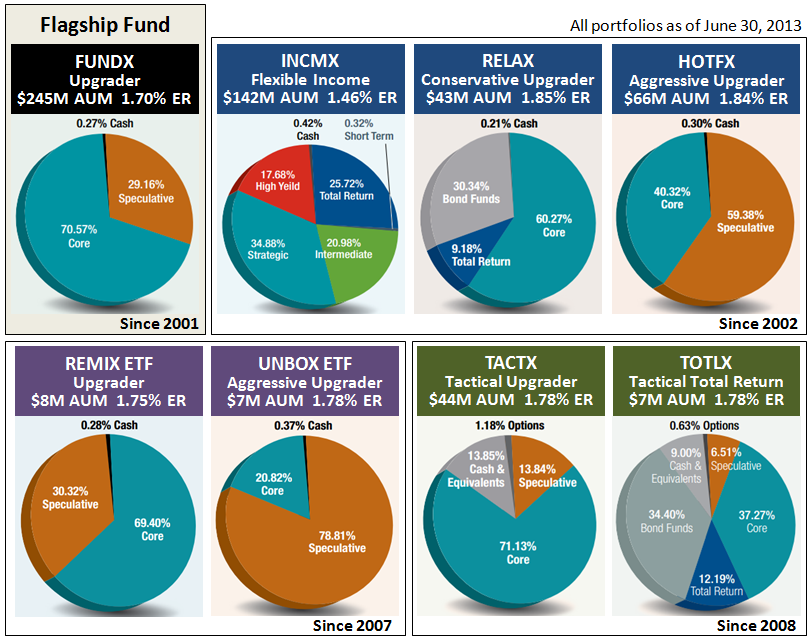

As of December 31, 2012, the advisor had nearly $900M AUM. About half is in several hundred individual accounts. The remaining AUM is held in the eight funds. All share similar upgrading strategies, but focused on different asset classes and objectives (e.g., fixed income bonds, moderate allocation, aggressive). The figure below summarizes top-level portfolio construction of each upgrader fund, as of June 30, 2013. Two are ETFs. Two others employ more tactical authority, like holding substantial cash or hedging to reduce volatility. FUNDX is the flagship equity fund with assets of $245M.

Managers

All FundX funds are managed by the same team, led by FundX’s president Janet Brown and its CIO Jason Browne. Ms. Brown joined the firm in 1978, became immersed with its founder’s methodology of ranking funds, assumed increasing money management responsibilities, became editor of their popular newsletter, then purchased the firm in 1997. Ms. Brown graduated from San Diego State with a degree in art and architecture. Mr. Browne joined the firm in 2000. He is a San Francisco State graduate who received his MBA from St Mary’s College. The other managers are Martin DeVault, Sean McKeon, and Bernard Burke. They too are seasoned in the study of mutual fund performance. That’s what these folks do.

Strategy Capacity and Closure

FUNDX would likely soft close between $1-1.5B and hard close at $2B, since the other funds and client portfolios use similar strategies. Mr. Browne estimates that the strategy itself has an overall capacity of $3B. In 2007, FUNDX reached $941M AUM. The portfolio today holds 26 underlying funds, with about 50% of assets in just seven funds, which means that the funds selected must have adequate liquidity.

Management Stake in the Fund

Ms. Brown has over $1M in FUNDX and between $100K and $1M in nearly all the firm’s funds. Mr. Browne too invests in all the funds, his largest investment is in tactically oriented TACTX where he has between $100K and $500K. The remaining team members hold as much as $500K in FUNDX and the fixed income INCMX, with smaller amounts in the other funds. None of the firm’s Independent Trustees, which include former President of Value Line, Inc. and former CEO of Rockefeller Trust Co., invest directly in any of the funds, but some hold individual accounts with the firm.

Opening Date

FUNDX was launched November 1, 2001. Its strategy is rooted in the NoLoad FundX Newsletter first published in 1976.

Minimum Investment

$1,000, reduced to $500 for accounts with an automatic investment plan.

Expense Ratio

1.70% as assets of $242 million (as of August 2013).

Comments

“Through bull and bear markets, Hulbert has emerged as the respected third-party authority on investment newsletters that consistently make the grade…for more than three decades, NoLoad FundX has emerged as a top performer in the Hulbert Financial Digest,” which is praise often quoted when researching FundX.

In a recent WSJ article, entitled “Chasing Hot Mutual-Fund Returns,” Mr. Hulbert summarizes results from a FundX study on fund selection, which considered over 300 funds at least two decades old. The study shows that since 1999, a portfolio based on top performing funds of the past year, like that used in the upgrader strategy, well outperforms against SP500 and a portfolio based of top performing funds of the last 10 years.

Hulbert Financial Digest does show the NoLoad FundX newsletter performance ranks among top of all newsletters tracked during the past 15 years and longer, but actually ranks it in lower half of those tracked for the last 10 years and shorter.

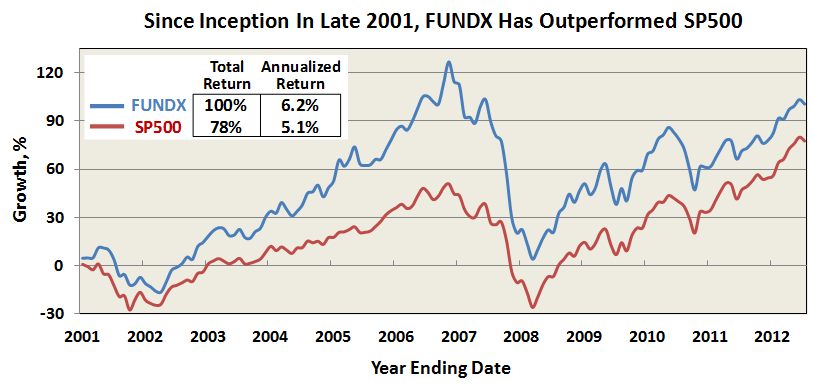

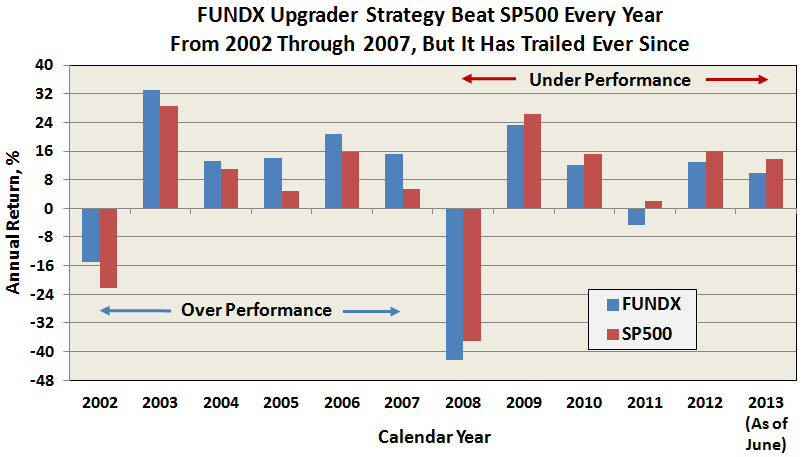

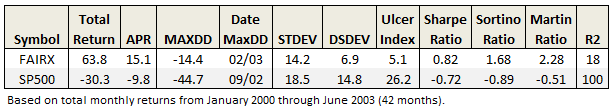

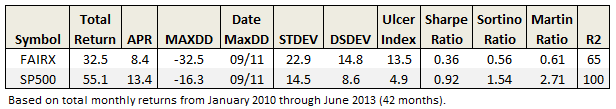

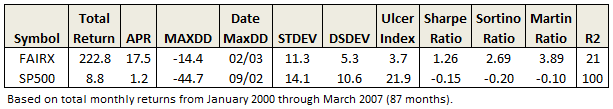

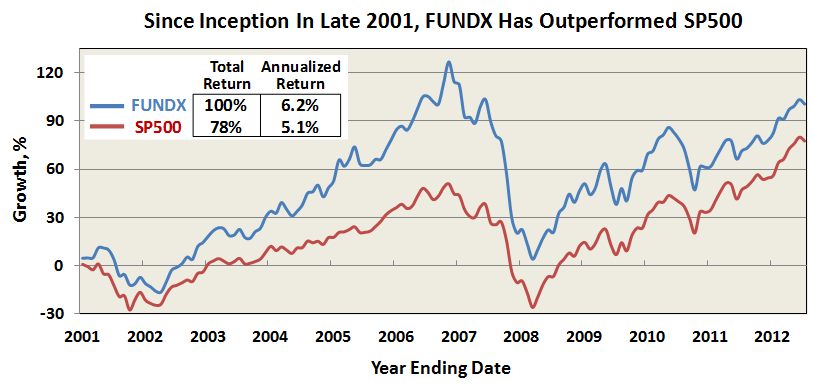

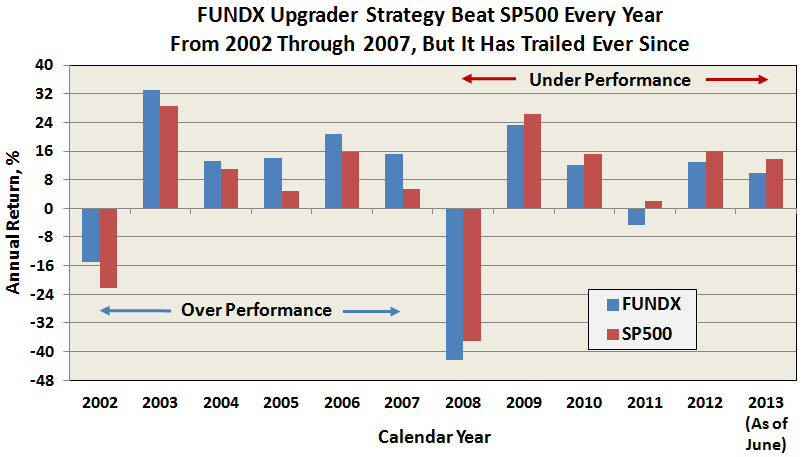

A look at FUNDX performance proper shows the flagship fund does indeed best SP500 total return. But a closer look shows its over-performance occurred only through 2007 and it has trailed every year since.

Comparisons against S&P 500 may be a bit unfair, since by design FUNDX can be more of an all-cap, global equity fund. The fund can incrementally shift from all domestic to all foreign and back again, with the attendant change in Morningstar categorization. But Ms. Brown acknowledged the challenge head-on in a 2011 NYT interview: “As much as people in the fund industry may want to measure their performance against a very narrowly defined index, the reality is that most people judge their funds against the SP500, for better or worse.”

Asked about the fall-off, Mr. Browne explained that the recent market advance is dominated by S&P 500. Indeed, many all-cap funds with flexible mandate, like FUNDX, have actually underperformed the last few years. So while the fund attempts to capture momentum of market leaders, it also maintains a level of diversification, at least from a risk perspective, that may cause it to underperform at times. Ideally, the strategy thrives when its more speculative underlying funds experience extended advances of 10 months and more, in alignment with similar momentum in its core funds.

Crucial to their process is maintaining the universe of quality no-load/load-waived funds on which to apply its upgrading strategy. “We used to think it was all about finding the next Yacktman, and while that is still partially true, it’s just as important to align with investment style leaders, whether it is value versus growth, foreign versus domestic, or large versus small.”

Today, “the universe” comprises about 1200 funds that offer appropriate levels of diversification in both investment style and downside risk. He adds that they are very protective when adding new funds to the mix in order to avoid excessive duplication, volatility, or illiquidity. With the universe properly established, the upgrading strategy is applied monthly. The 1200 candidate funds get ranked based on performance of the past 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Any holding that is no longer in the top 30% of its risk class gets replaced with the current leaders.

Both Ms. Brown and Mr. Browne make to clear that FUNDX is not immune to significant drawdown when the broad market declines, like in 2008-2009. In that way, it is not a timing strategy. That technique, however, can be used in the two more tactical upgrader funds TACTX and TOTLX.

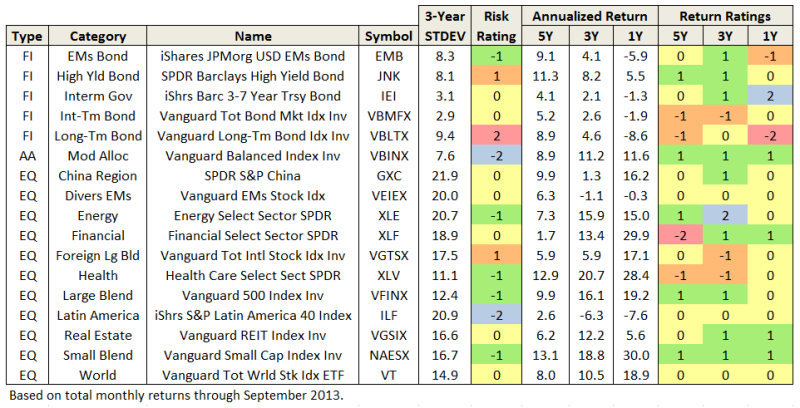

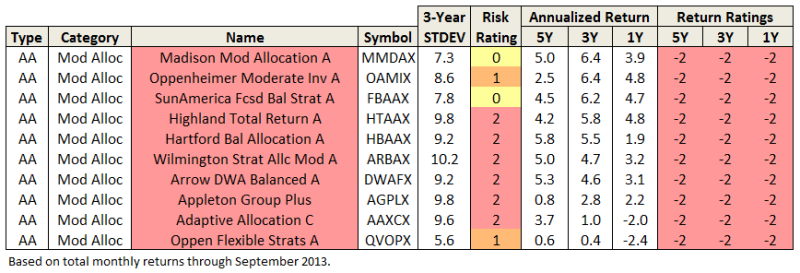

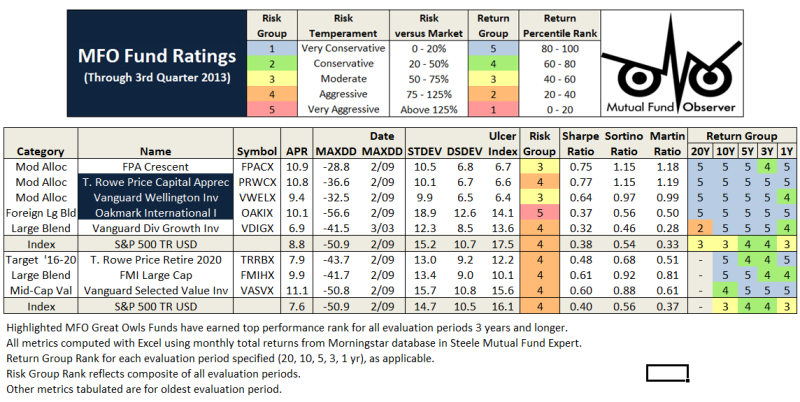

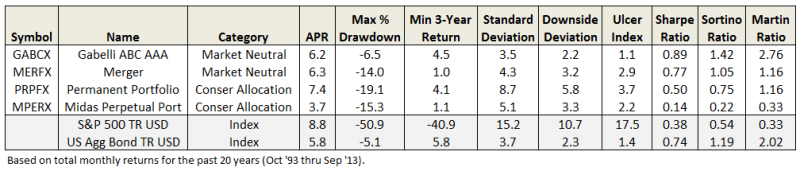

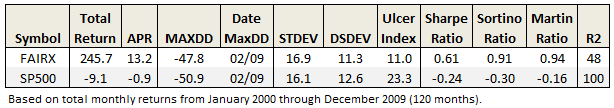

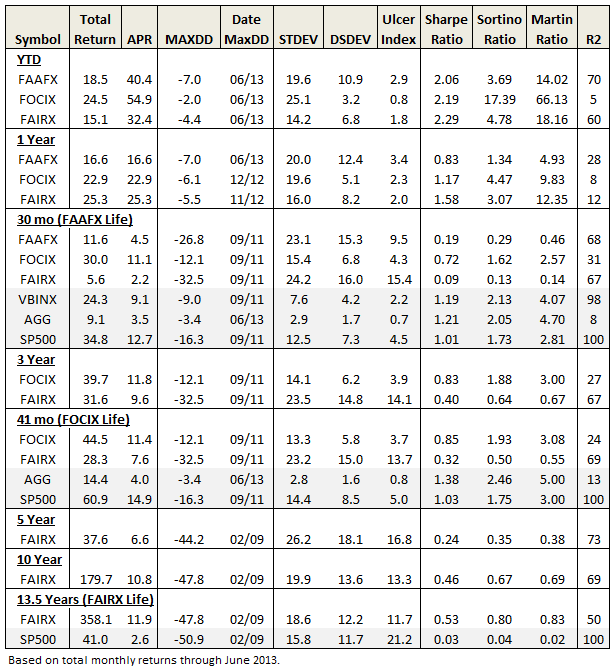

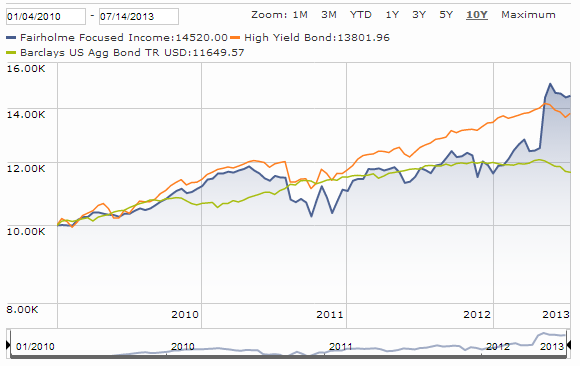

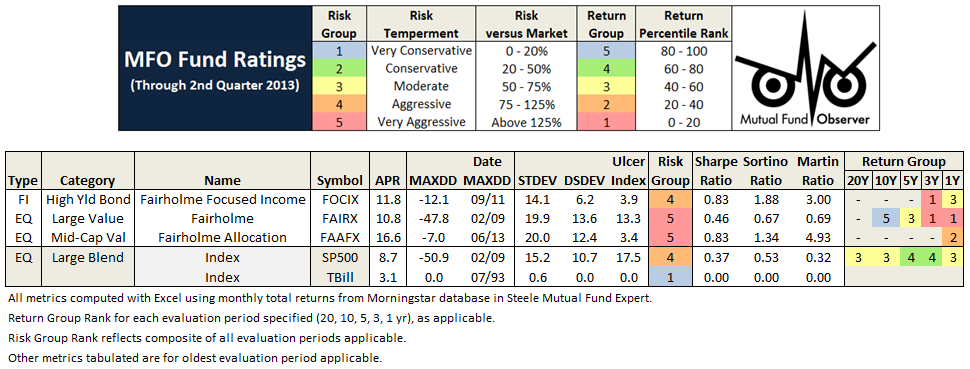

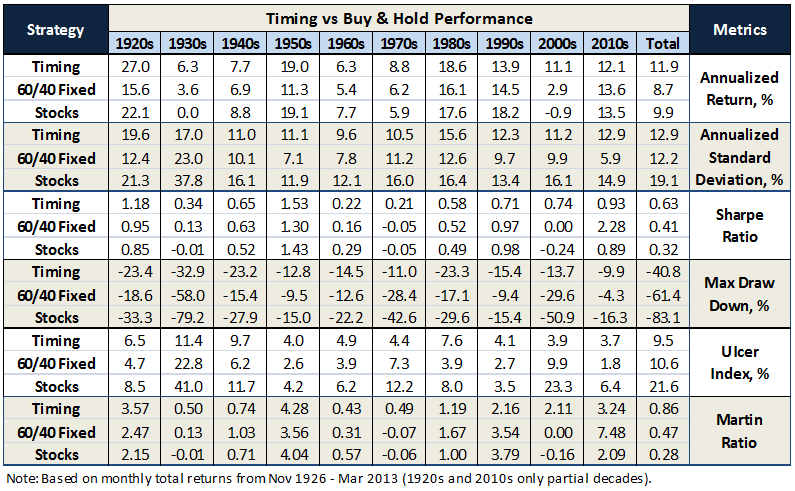

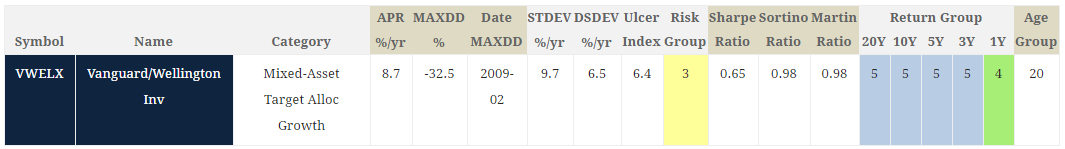

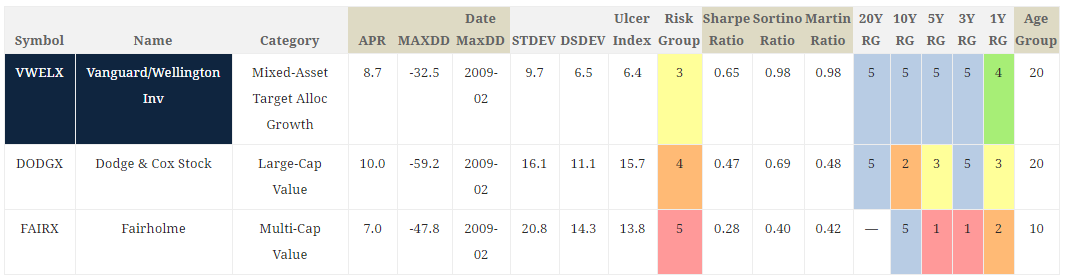

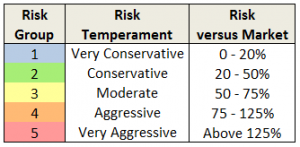

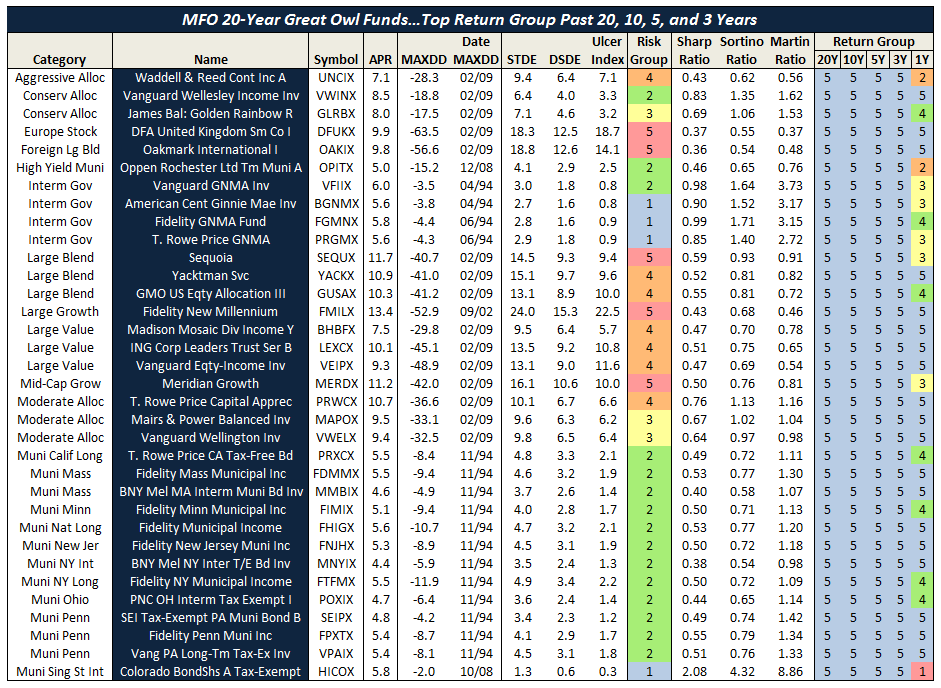

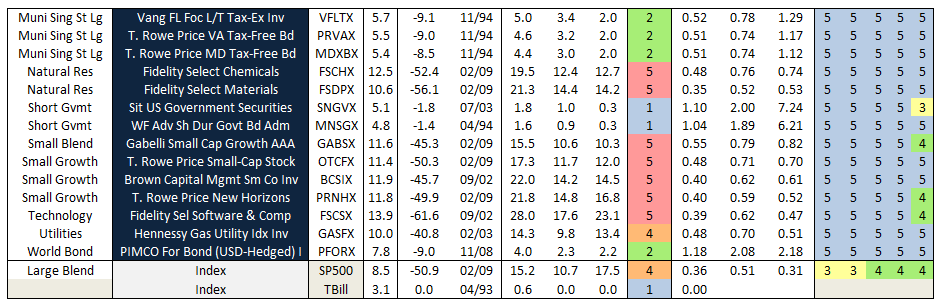

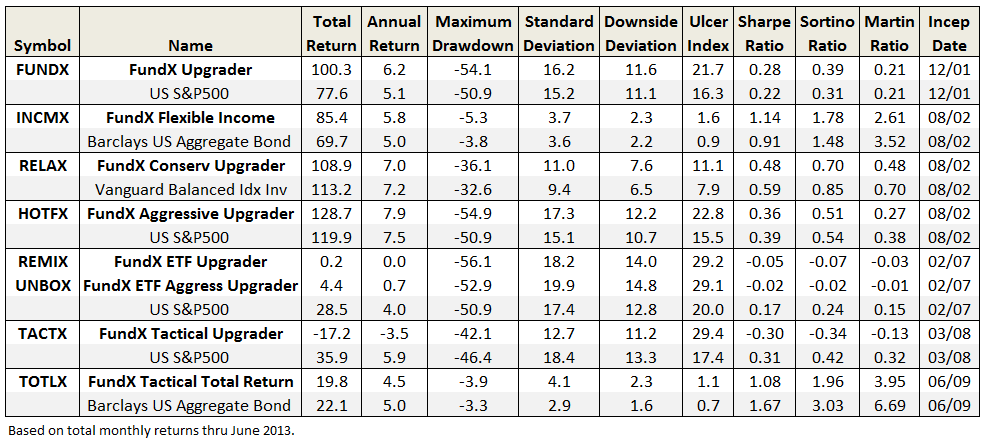

The table below summarizes lifetime risk and return numbers for FUNDX, as well as the other upgrader funds. Reference indices over same periods are included for comparison. Over longer term the four upgrader funds established by 2002 have held-up quite well, if with somewhat higher volatility and maximum drawdown than the indices. Both ETFs have struggled since inception, as has TACTX.

I suspect that few understand more about mutual fund performance and trends than the folks at FundX. Like many MFO readers, they fully appreciate most funds do not lead persistently and that hot managers do not stay on-top. Long ago, in fact, FundX went on record that chronic underperformance of Morningstar’s 5-star funds is because time frames considered for its ratings “are much too long to draw relevant conclusions of how a fund will do in the near future.” Better instead to “invest based on what you can observe today.” And yet, somewhat ironically, while the upgrading strategy has done well in the long term, FUNDX too can have its time in the barrel with periods of extended underperformance.

While the advisor campaigns against penalizing funds for high expenses, citing that low fees do not guarantee top performance, it’s difficult to get past the high fees of FUNDX and the upgrader funds. The extra expense layer is typical with fund-of-funds, although funds which invest solely in their own firm’s products (e.g., the T. Rowe Price Spectrum Funds and Vanguard STAR VGSTX) are often exceptions.

Bottom Line

It is maddeningly hard, as Value Line and FundX have certainly discovered, to translate portfolios which look brilliant in newsletter systems into actual mutual funds with distinguished records. The psychological quirks which affect all investors, high operating expenses, and the pressure to gain and retain substantial AUM all erode even the best-designed system.

It might well be that FUNDX’s weak performance in the past half-decade is a statistical anomaly driven by the failure of its system to react quickly enough to the market’s bottoming in the first quarter of 2009 and its enormous surge in the second. Those sorts of slips are endemic to quant funds. Nonetheless, the fund has not outperformed a global equity benchmark two years in a row for more than a decade and trails that benchmark by about 1% per year for the decade. The fact that the FundX team faces those challenges despite access to an enormous amount of data, a clear investment discipline and access to a vast array of funds serves as a cautionary tale to all of us who attempt to actively manage our fund portfolios.

Website

The FundX Investment Group, which links to its investment services, newsletter, and upgrader funds. The newsletter, which can be subscribed on-line for $89 annual, is chock full of good information.

FundX Upgrader Website, this also lists the 2013 Q3 report under the Performance tab.

Fact Sheet

Charles/31Aug2013

Roy Weitz first published the legacy Three Alarm fund list in 1996. He wanted to help investors decide when to sell mutual funds. Being on the list was not an automatic sell, but a warning signal to look further and see why.

Roy Weitz first published the legacy Three Alarm fund list in 1996. He wanted to help investors decide when to sell mutual funds. Being on the list was not an automatic sell, but a warning signal to look further and see why.