Objective and Strategy:

The fund’s investment objective is long-term capital appreciation, which it pursues by investing in 25-30 U.S. large cap companies. Its intent is to find companies so excellent that they might be held for decades. Their criteria for such firms are ones that meet an economic need, have a long history of profitability, a strong competitive position, a lot of free cash flow and a stock selling at a discount. Shareholder-friendly management, strong insider ownership and a strong balance sheet are all positives but not requirements.

Adviser:

Smead Capital Management, whose motto is “Only the Lonely Can Play.” The firm advises Smead Value and $150 million in of separate accounts.

Managers:

William W. Smead and Tony Scherrer. Mr. Smead, founder and CEO of the adviser, has 33 years of experience in the investment industry and was previously the portfolio manager of the Smead Investment Group of Wachovia Securities. Mr. Scherrer joined the firm in 2008 and was previously the Vice President and Senior Portfolio Manager at U.S. Trust and Harris Private Bank. He has 18 years of professional investment experience.

Management’s Stake in the Fund:

Mr. Smead has over $1 million invested in the fund and Mr. Scherrer has between $100,000 and $500,000.

Opening date:

January 2, 2008

Minimum investment:

$3,000 initially, $500 subsequently.

Expense ratio:

1.25% on assets of about $4.7 Billion, as of July 2023.

Comments:

Well, there certainly aren’t a lot of moving parts here. In a world dominated by increasingly complex (multi-asset, multi-strategy, multi-cap, multi-manager) products, Smead Value stands out for a refreshingly straightforward approach: Research. Buy. Hold.

Mr. Smead believes that U.S. blue chip stocks are about the best investment you can make. Not just now or this decade or over the past 25 years. The best, pretty much ever. He realizes there are a lot of very smart guys who disagree with him; “the brilliant pessimists” he calls them. He seems to have three beliefs about them:

- They might be right at a macro level, but that doesn’t mean that they’re offering good investment advice. He notes, for example, that the tech analysts were right in the late 1990s: the web was going to change everything. Unfortunately, that Big Picture insight did not convert to meaningful investing advice.

- Their pessimism is profitable – to him. Anything scarce, he argues, goes up in value. As more and more Big Thinkers become pessimistic, optimism becomes more valuable. The old adage is “stocks climb a wall of worry” and the pessimists provide the wall.

- Their pessimism is unprofitable to their investors. He notes, as a sort of empirical test, that few pessimist-driven strategies have actually made money.

Even managers who don’t buy pessimism are, he believes, twitchy. They buy and sell too quickly, eroding gains, driving up costs and erasing whatever analytic advantage they might have held. The investing world is, he claims, 35% passive, 5% active … and 60% too active.

He’s even more dismissive of many investing innovations. Commodities, he notes, are not more an “asset class” than blackjack is and futures contracts than a nine-month bet. Commodity investing is a simple bet on the future price of an inanimate object that such bets have, for over 200 years, turned out badly: sharp price spikes have inevitably been followed by price crashes and 20-year bear markets.

His view of China is scarcely more sanguine.

His alternative? Find excellent companies. Really excellent ones. Wait and wait and wait until their stock sells at a discount. Buy. Hold. (His preferred time frame is “10 years to forever”.) Profit.

That’s about it.

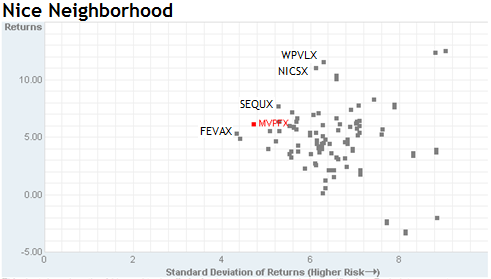

And it works. A $10,000 investment in Smead Value at inception would be worth $13,600 by the end of June 2013; a similar investment in its average peer would have grown to only $11,800. That places it in the top 1-2% of large cap core funds. It has managed that return with lower volatility (measured by beta, standard deviation and downside capture ratios) than its peers. It’s not surprising that the fund has earned five stars from Morningstar and a Lipper Leaders designation from Lipper.

Bottom Line:

Mr. Smead is pursuing much the same logic as the founders of the manager-less ING Corporate Leaders Fund (LEXCX). Buy great companies. Do not sell. Investors might reasonably complain about the expenses attached to such a low turnover strategy (though he anticipates dropping them by 15 basis points in 2013), but they don’t have much grounds for complaining about the results.

Fund website:

[cr2013]