Objective and strategy

The managers pursue long-term growth of capital and income by investing in a fairly compact portfolio of international small cap stocks. Their goal is to find the most undervalued streams of sustainable cash flow that they can. The managers start with quantitative screens to establish country and industry rankings, then a second set of valuation screens to identify a pool of potential buys. There are around 17,000 unique companies between $50 million – $3 billion in market cap. Around 400 companies have been passing the screens consistently for the past many months. Portfolio companies are selected after intensive fundamental review. The portfolio typically holds between 75-100 stocks representing at least 10 countries.

Adviser

Pear Tree Advisors is an affiliate of U.S. Boston. U.S. Boston was founded in 1969 to provide wealth management services to high net worth individuals. In 1985, they began to offer retail funds, originally under the Quantitative Funds name, each of which is sub-advised by a respected institutional manager. There are six funds in the family, two domestic (U.S. large cap quality and U.S. small cap) and four international (international multi cap value, international small cap value, and two emerging markets funds). The sub-adviser for this fund is Polaris Capital Management, LLC. Founded in 1995, Polaris describes itself as a “global value equity manager.” The firm is owned by its employees and, as of December 2014, managed $5.6 billion for institutions, retirement plans, insurance companies, foundations, endowments, high-net-worth individuals, investment companies, corporations, pension and profit sharing plans, pooled investment vehicles, charitable organizations, state or municipal governments, and limited partnerships.

Manager

Bernard Horn, Sumanta Biswas and Bin Xiao. Mr. Horn is Polaris’s founder, president, chief investment officer and lead manager on Polaris Global Value Fund. He is, on whole, well-known and well-respected in the industry. Day to day management of the fund, including security selection and position sizing, is handled by Messrs. Biswas and Xiao. Mr. Biswas joined the firm as an intern (2001), was promoted to research analyst (2002), then assistant portfolio manager (2004), vice president (2005) and Partner (2007). Mr. Xiao joined the firm as an analyst in 2006 and was promoted to assistant portfolio manager in 2012. Both are described as investment generalists. The team manages about $5.6 billion together, including the Polaris Global Value Fund (PGVFX) and subadvisory of PearTree Polaris Foreign Value (QFVOX) the value portion of PNC International Equity (PMIEX), and other multi-manager funds.

Strategy capacity and closure

Between $1 – 1.5 billion, an amount that might rise or fall as market conditions change. The number of international small cap stocks is growing, up by nearly 100% in the past decade and the number of international IPOs is growing at ten times the U.S. rate.

Size constraint is ‘time’ dependent. The Fund objective is to beat the benchmark with lower than benchmark risk (risk is the ITD annualized beta of the portfolio). The managers’ past experience suggests that a portfolio of around 75-100 stocks provides an acceptable risk/return trade-off. Overlaying a liquidity parameter allowed the Fund to reach the $1- $1.5 billion in potential assets under management.

However the universe of companies is expanding and liquidity conditions keep changing. Fund managers suggested that they are open to increasing the number of companies in the portfolio as long as the new additions do not compromise their risk/return objective. So, the main constraining factor guiding fund size is how many investable companies the market is offering at any given point in time.

Active share

“Active share” measures the degree to which a fund’s portfolio differs from the holdings of its benchmark portfolio. High active share indicates management which is providing a portfolio that is substantially different from, and independent of, the index. An active share of zero indicates perfect overlap with the index, 100 indicates perfect independence. The advisor has not calculated the active share for its funds but the managers note that the high tracking error and low correlation with its benchmark implies a high active share.

Management’s stake in the fund

Mr. Horn has over $1 million in the fund and owns about 5% of the fund’s institutional shares. Messrs. Xiao and Biswas each have been $50,000-100,000 invested here; “we have,” they report, “all of our personal investments in our funds.” Three of the four independent trustees have no investment in the fund; one of them has over $100,000.

Opening date

May 1, 2008.

Minimum investment

$2,500, reduced to $1,000 for tax-advantaged accounts. The institutional minimum is $1 million. Roger Vanderlaan, one of the Observer’s readers, reports that the institutional shares of this fund, as well as the two others sub-advised by Polaris for Pear Tree, are all available from Vanguard for a $10,000 initial purchase though they do carry a transaction fee.

Expense ratio

1.04% on assets of $995.3 million for the institutional class shares, 1.41% for investor class shares, as of July 2023.

Comments

There are three, and only three, great international small cap funds: Wasatch International Opportunities (WAIOX), Grandeur Peak International Opportunities (GPIOX) and Pear Tree Polaris Foreign Value Small Cap.

What do we mean by “small cap”? We looked for funds that invested in (brace yourselves) small and micro-cap stocks. One signal of that is the fund’s average market cap; we targeted funds at $2 billion or less since about 80% of all stocks are below that threshold. Of the 90 funds in the Morningstar’s international small- to mid-cap categories, only 17 actually had portfolios dominated by small cap stocks.

What do we mean by “great”? We started by looking at the returns of those 17 funds over the past one-, three- and five-year periods. Two things were clear: the same names dominated the top four spots over and over and only three funds managed to make money over the past year (through the end of January, 2015). And the fourth fund, Brandes International Small Cap Equity “A”(BISAX) looked strong except (1) it sagged over the past year and (2) the great bulk of its track record, from inception in August 1996 through January 2012, occurred when it was organized as “a private investment commingled fund.” The SEC allowed BISAX to assume the performance record of the prior fund, but questions always arise when an investment vehicle moves from one structure to another.

|

1 yr |

3 yr |

5 yr |

Risk |

Assets ($M) |

|

|

WAIOX |

8.8 |

15.8 |

12.5 |

Average |

342 |

|

GPIOX |

4.3 |

18.9 |

— |

Average |

775 – closed |

|

QUSOX |

5.4 |

16.8 |

10.4 |

Below average |

302 |

|

BISAX |

-2.8 |

15.5 |

11.2 |

n/a |

611 |

(all returns are through January 30, 2015)

That’s leads to two questions: should you consider adding any international small cap exposure to your portfolio? And should you especially consider adding Pear Tree Polaris to it? For many investors, the answer to both is “yes.”

Why international small cap?

There are four reasons to consider adding international small cap exposure.

- They are a large opportunity set. About 80% of the world’s stocks have market caps below $2 billion. Grandeur Peak estimates that there are 29,000 investible small cap stocks worldwide, 25,000 being outside of the U.S.

- The opportunity set is growing. Since 2000, over 90% of IPOs have been filed outside of the US. Meanwhile, the number of US listed stocks declined from 9,000 to under 5,000 in the first 12 years of the 21stcentury. As markets deepen and the middle class grows in many emerging nations, the number of small caps will continue to climb.

- You’re ignoring them, and so is almost everyone else. As we noted above, there are fewer than 20 true international small cap funds. Most of the funds that bear the designation actually invest most of their money into mid-caps and often a lot into large caps as well. According to Morningstar, the average small- to mid-cap international growth fund has 24% of its money in small caps and 19% in large caps. International small value and blend funds invest, on average, 35-38% in small caps. Broad international indexes have only 3-4% of their weightings in small caps, so those won’t help you either. Given that the average individual US investor has an 80% allocation to US stocks, it’s likely that you have under 1% of your portfolio in international small caps.

- They are a valuable opportunity set. There are three factors that make them valuable. They are independent: they are weakly correlated with the US market, international large caps or each other, they are rather state-owned and they are driven more by local conditions than by government fiat or global macro trends. They are mispriced. Because of liquidity constraints, they’re ignored by large institutions and index-makers. The average international microcap is covered by one analyst, the average small cap by four, and 20% of international small caps have no analyst coverage. Across standard trailing time periods, they outperform international large caps with higher Sharpe and Sortino ratios. Finally, they are the last, best haven of active management. The average international small cap manager outperforms his or her benchmark by 200-300 bps. Really good ones can add a multiple of that.

Why Pear Tree Polaris?

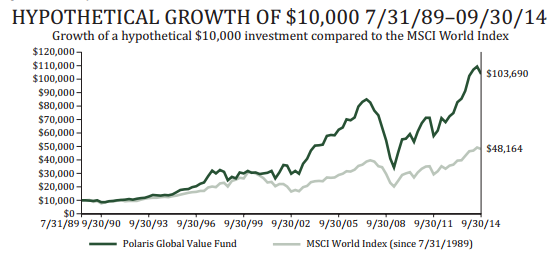

While this fund is relatively new, the underlying discipline has been in place for 30 years and has been on public display in Polaris Global Value Fund (PGVFX) for 17 years. The core strategy is disciplined, simple and repeatable. They’re looking to buy the most undervalued companies in the world, based on their calculation of a firm’s sustainable free cash flow discounted by conditions in the firm’s home country. They look, in particular, at free cash flow from operations minus the capital expenditures needed to maintain those operations. By using conservative assumptions about growth and a high discount rate, the system builds a wide margin of safety into its modeling.

The managers overlay those factors with an additional set of risk control in recognition of the fact that individual international small cap stocks are going to be volatile, no matter how compelling the underlying firm’s business model and practices.

Mr. Biswas remembers Mr. Horn’s warning, long ago, that emerging markets stocks are intrinsically volatile. Thinking that he’d found a way around the volatility trap, Biswas targeted a portfolio of defensive essentials, such as rice, fish and textbooks, and then discovered that even “essentials” might plummet 80% one year then rocket 90% the next.

Among the risk management tools they use are position sizing and an attempt to understand what really matters to the firm’s prospects. The normal position size is 1.6% of assets, but they might invest just half of that in a stock with limited liquidity.

They are typically overweight companies in five sectors: utilities, telecom, healthcare, energy and materials. The defensive sectors of utilities, telecom and healthcare are only 15% of the 17,000 companies in the small-cap universe. Energy is less than 5% of the same universe. Materials is adequately represented in the 17,000 company set. However, finding value opportunities (businesses with stable cash flows with limited down side risk at high discount rates) in these sectors is often challenging. In view of the above, they typically overweight companies in these 5 sectors to ensure greater diversification and lower portfolio volatility.

Because small companies are often monoline, that is they do or make just one thing, their prospects are easier to understand than are those of larger firms, at least once you understand what to pay attention to. Mr. Biswas says that, for many of these firms, you need to understand just three or four key drivers. The other factors, he says, have “low marginal utility.” If you can simplify the firm’s business model, identify the drivers and then learn how to talk with management about them, you can quickly verify a stock’s fundamental attractiveness.

Because those factors change slowly and the portfolio is compact with low turnover (about 10% per year so far, though that might rise over time to the 20-30% range), it’s entirely possible for a small team to track their investible universe.

Bottom Line

This is about the most consistent and most consistently risk-conscious international small cap fund around. It has, since inception, maintained its place among the best funds in its universe and has handily outperformed both the only Gold-rated international small value fund (DFA International Small Value DSIVX) and its average peer by a lot. It has done that while compiling the group’s most attractive risk-return profile. Any fund that invests in such risky assets comes with the potential for substantial losses. That includes this fund. The managers have done an uncommonly good job of anticipating those risks and executing a system that is structurally risk-averse. While they will not always lead the pack, they will – on average and over time – serve their investors well. They deserve a place near the top of the due diligence list for investors interested in risk assets that have not yet run their course.

Fund website

Pear Tree Polaris Foreign Value Small Cap. For those looking for a short introduction to the characteristics of international or global small caps as an asset class, you might consider Chris Tessin’s article “International Small Cap A Missed Opportunity” from Pensions & Investments (2013)

(2023)

[cr2015]

Okay, if that one six quarter period didn’t exist, Polaris would be about the world’s finest fund and Mr. Horn wouldn’t have any explaining to do.

Okay, if that one six quarter period didn’t exist, Polaris would be about the world’s finest fund and Mr. Horn wouldn’t have any explaining to do.