“Cynicism is an unpleasant way of saying the truth.”

Lillian Hellman

Current Events:

While we may be where we are, it is worth a few moments to talk about how we got here. In recent months the dichotomy between the news agendas of the U.S. financial press and the international press has become increasingly obvious. At the beginning of August, a headline on the front page of the Financial Times read, “One Trillion Dollars in Capital Flees Emerging Markets.” I looked in vain for a similar story in The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. There were many stories about the next Federal Reserve meeting and whether they would raise rates, stories about Hillary Clinton’s email server, and stories about Apple’s new products to come, but nothing about that capital flight from the emerging markets.

We then had the Chinese currency devaluation with varying interpretations on the motivation. Let me run a theme by you that was making the rounds of institutional investors outside of the U.S. and was reported at that time. In July there was a meeting of the International Monetary Fund in Europe. One of the issues to be considered was whether or not China’s currency, the renminbi, would be included in the basket of currencies against which countries could have special drawing (borrowing) rights. This would effectively have given the Chinese currency the status of a reserve currency by the IMF. The IMF’s staff, whose response sounded like it could have been drafted by the U.S. Treasury, argued against including the renminbi. While the issue is not yet settled, the Executive Directors accepted the staff report and will recommend extending the lifespan of the current basket, now set to expire December 31, until at least September 2016. At the least, that would lock out the renminbi for another year. The story I heard about what happened next is curious but telling. The Chinese representative at the meeting is alleged to have said something like, “You won’t like what we are going to do next as a result of this.” Two weeks after the conclusion of the IMF meeting, we then had the devaluation of China’s currency, which in the minds of some triggered the increased volatility and market sell-offs that we have seen since then.

I know many of you are saying, “Pshaw, the Chinese would never do anything as irrational as that for such silly reasons.” And if you think that dear reader, you have yet to understand the concept of “Face” and the importance that it plays in the Asian world. You also do not understand the Chinese view of self – that they are a Great People and a Great Nation. And, that we disrespect them at our own peril. If you factor in a definition of long-term, measured in centuries, events become much more understandable.

I know many of you are saying, “Pshaw, the Chinese would never do anything as irrational as that for such silly reasons.” And if you think that dear reader, you have yet to understand the concept of “Face” and the importance that it plays in the Asian world. You also do not understand the Chinese view of self – that they are a Great People and a Great Nation. And, that we disrespect them at our own peril. If you factor in a definition of long-term, measured in centuries, events become much more understandable.

One must read the world financial press regularly to truly get a picture of global events. I suggest the Financial Times as one easily accessible source. What is reported and considered front page news overseas is very different from what is reported here. It seems on occasion that the bobble-heads who used to write for Pravda have gotten jobs in public relations and journalism in Washington and Wall Street.

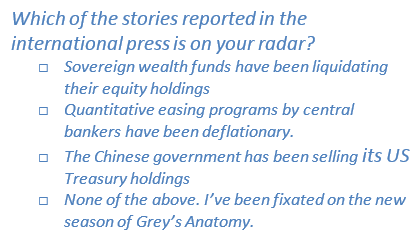

One example – this week the Financial Times reported the story that many of the sovereign wealth funds (those funds established by countries such as Kuwait, Norway, and Singapore to invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets, for pension, infrastructure or healthcare, among other things), have been liquidating investments. And in particular, they have been liquidating stocks, not bonds. Another story making the rounds in Europe is that the various “Quantitative Easing” programs that we have seen in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, are, surprise, having the effect of being deflationary. And in the United States, we have recently seen the three month U.S. Treasury Bill trading at negative yields, the ultimate deflationary sign. Another story that is making the rounds – the Chinese have been selling their U.S. Treasury holdings and at a fairly rapid clip. This may cause an unscripted rate rise not intended or dictated by the Federal Reserve, but rather caused by market forces as the U.S. Treasury continues to come to market with refinancing issues.

One example – this week the Financial Times reported the story that many of the sovereign wealth funds (those funds established by countries such as Kuwait, Norway, and Singapore to invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets, for pension, infrastructure or healthcare, among other things), have been liquidating investments. And in particular, they have been liquidating stocks, not bonds. Another story making the rounds in Europe is that the various “Quantitative Easing” programs that we have seen in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, are, surprise, having the effect of being deflationary. And in the United States, we have recently seen the three month U.S. Treasury Bill trading at negative yields, the ultimate deflationary sign. Another story that is making the rounds – the Chinese have been selling their U.S. Treasury holdings and at a fairly rapid clip. This may cause an unscripted rate rise not intended or dictated by the Federal Reserve, but rather caused by market forces as the U.S. Treasury continues to come to market with refinancing issues.

The collapse in commodity prices, especially oil, will sooner or later cause corporate bodies to float to the surface, especially in the energy sector. Counter-party (the other side of a trade) risk in hedging and lending will be a factor again, as banks start shrinking or pulling lines of credit. Liquidity, which was an issue long before this in the stock and bond markets (especially high yield), will be an even greater problem now.

The SEC, in response to warnings from the IMF and the Federal Reserve, has unanimously (which does not often happen) called for rules to prevent investors’ demands for redemptions in a market crisis from causing mutual funds to be driven out of business. Translation: don’t expect to get your money as quickly as you thought. I refer you to the SEC’s Proposal on Liquidity Risk Management Programs.

I mention that for the better of those who think that my repeated discussions of liquidity risk is “crying wolf.”

“It’s a Fine Kettle of Fish You’ve Gotten Us in, Ollie.”

I have a friend who is a retired partner from Wellington in Boston (actually I have a number of friends who are retired partners from there). Wellington is not unique in that, like Fidelity, it is very unusual for an analyst or money manager to

stay much beyond the age of fifty-five. So I asked him one day how he had his retirement investments structured, hoping I might get some perspective into thinking on the East Coast, as well as perhaps some insights into Vanguard’s products, given the close relationship between Vanguard and Wellington. His answer surprised me – “I have it all in index funds.” I asked if there were any particular index funds. Again the answer surprised me. “No bond funds, and actually only one index fund – the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund.” And when I asked for further color on that, the answer I got was that he was not in the business full time anymore, looking at markets and security valuations every day, so this was the best way to manage his retirement portfolio for the long-term at the lowest cost. Did he know that there were managers, that 10% or so, who consistently (or at least for a while, consistently) outperform the index? Yes, he was aware that such managers were out there. But at this juncture in his life he did not think that he either (a) had the time, interest, and energy to devote to researching and in effect “trading managers” by trading funds and (b) did not think he had any special skill set or insights that would add value in that process that would justify the time, the one resource he could not replace. Rather, he knew what equity exposure he wanted over the next twenty or thirty years (and he recognized that life expectancies keep lengthening). The index fund over that period of time would probably compound at 8% a year as it had historically with minimal transaction costs and minimal tax consequences. He could meet his needs for a diversified portfolio of equities at an expense ratio of five basis points. The rest of his assets would be in cash or cash equivalents (again, not bonds but rather insured certificates of deposit).

I have talked in the past about the need to focus on asset allocation as one gets older, and how index funds are the low cost way to achieve asset diversification. I have also talked about how your significant other may not have the same interest or ability in managing investments (trading funds) after you go on to your just reward. But I have not talked about the intangible benefits from investing in an index fund. They lessen or eliminate the danger of portfolio manager or analyst hubris blowing up a fund portfolio with a torpedo stock. They also eliminate the divergence of interests between the investment firm and investors that arises when the primary focus is running the investment business (gathering assets).

What goes into the index is determined not by the entity running the fund (although they can choose to create their own index, as some of the European banks have done, and charge fees close to 2.00%). There is no line drawn in the sand because a portfolio manager has staked his public reputation on his or her genius in investing in a particular entity. There is also no danger in an analyst recommending sale of an issue to lock in a bonus. There is no danger of an analyst recommending an investment to please someone in management with a different agenda. There is no danger of having a truncated universe of opportunities to invest in because the portfolio manager has a bias against investing in companies that have women chief executive officers. There is no danger of stock selection being tainted because a firm has changed its process by adding an undisclosed subjective screening mechanism before new ideas may be even considered. While firm insiders may know these things, it is a very difficult thing to learn them from the outside.

Is there a real life example here? I go back to the lunch I had at the time of the Morningstar Conference in June with the father-son team running a value fund out of Seattle. As is often the case, a subject that came up (not raised by me) was Washington Mutual (WaMu, a bank holding company that collapsed in 2008, trashing a bunch of mutual funds when it did). They opined how, by being in Seattle (a big small town), they had been able to observe up close and personally how the roll-up (which was what Washington Mutual was) had worked until it didn’t. Their observation was that the Old Guard, who had been at the firm from the beginning with the chair of the board/CEO had been able to remind him that he put his pants on one leg at a time. When that Old Guard retired over time, there was no one left who had the guts to perform that function, and ultimately the firm got too big relative to what had driven past success. Their assumption was that their Seattle presence gave them an edge in seeing that. Sadly, that was not necessarily the case. In the case of many an investment firm, Washington Mutual became their Stalingrad. Generally, less is more in investing. If it takes more than a few simple declarative sentences to explain why you are investing in a business, you probably should not be doing it. And when the rationale for investing changes and lengthens over time, it should serve as a warning.

I suspect many of you feel that the investment world is not this way in reality. For those who are willing to consider whether they should rein in their animal spirits, I commend to you an article entitled “Journey into the Whirlwind: Graham-and-Doddsville Revisited” by Louis Lowenstein (2006) and published by The Center for Law and Economic Studies at Columbia Law School. (Lowenstein, father of Roger Lowenstein, looks at the antics of large growth managers and conclude, “Having attracted, not investors, but speculators trying to catch the next new thing, management got the shareholders they deserved.” Snowball). When I look at the investment management profession today, as well as its lobbying efforts to prevent the imposition of stricter fiduciary standards, I question whether what they really feel in their hearts is that the sin of Madoff was getting caught.

The End

Is there anything I am going to say this month that may be useful to the long-term investor? There is at present much fear abroad in the land about investing in emerging and frontier markets today, driven by what has happened in China

and the attendant ripple effect. The question I will pose for your consideration is this. What if five years from now it becomes compellingly obvious that China has become the dominant economic force in the world? Since economic power ultimately leads to political and military power, China wins. How should one be investing a slice of one’s assets (actively-managed of course) today if one even thinks that this is a remotely possible outcome? Should you be looking for a long-term oriented, China-centric fund?

There is one other investment suggestion I will make that may be useful to the long-term investor. David has raised it once already, and that is dedicating some assets into the micro-cap stock area. Focus on those investments that are in effect too small and extraordinarily illiquid in market capitalization for the big firms (or sovereign wealth funds) to invest in and distort the prices, both coming and going. Micro-cap investing is an area where it is possible to add value by active management, especially where the manager is prepared to cap the assets that it will take under management. Look for managers or funds where the strategy cannot be replicated or imitated by an exchange traded fund. Always remember, when the elephants start to dance, it is generally not pleasant for those who are not elephants.

Edward A. Studzinski

P.S. – Where Eagles Dare

The fearless financial writer for the New York Times, Gretchen Morgenson, wrote a piece in the Sunday Times (9/27/2015) about the asset management company First Eagle Investment Management. The article covered an action brought by the SEC for allegedly questionable marketing practices under the firm’s mutual funds’ 12b-1 Plan. Without confirming or denying the allegations, First Eagle settled the matter by paying $27M in disgorgement and interest, and $12.5M in fines. With approximately $100B in assets generating an estimated $900+M in revenues annually, one does not need to hold a Tag Day for the family-controlled firm. Others have written and will write more about this event than I will.

Of more interest is the fact that Blackstone Management Partners is reportedly purchasing a 25% stake in First Eagle that is being sold by T/A Associates of Boston, another private equity firm. As we have seen with Matthews in San Francisco, investments in investment management firms by private equity firms have generally not inured to the benefit of individual investors. It remains to be seen what the purpose is of this investment for Blackstone. Blackstone had had a right-time, right-strategy investment operation with its two previously-owned closed-end funds, The Asia Tigers Fund and The India Fund, both run by experienced teams. The funds were sold to Aberdeen Asset Management, ostensibly so Blackstone could concentrate on asset management in alternatives and private equity. With this action, they appear to be rethinking that.

Other private equity firms, like Oaktree, have recently launched their own specialist mutual funds. I would note however that while the First Eagle Funds have distinguished long-term records, they were generated by individuals now absent from the firm. There is also the question of asset bloat. One has to wonder if the investment strategy and methodology could not be replicated by a much lower cost (to investors) vehicle as the funds become more commodity-like.

Which leaves us with the issue of distribution – is a load-based product, going through a network of financial intermediaries, viable, especially given how the Millennials appear to make their financial decisions? It remains to be seen. I suggest an analogy worth considering is the problem of agency-driven insurance firms like Allstate. Allstate would clearly like to not have an agency distribution system, and would make the switch overnight if it could without losing business. It can’t, because too much of the book of business would leave. And yet, when one looks at the success of GEICO and Progressive in going the on-line or 1-800 route, one can see the competitive disadvantage, especially in automobile insurance, which is the far more profitable business to capture. It remains to be seen how distribution will evolve in the investment management world, especially as pertains to funds. As fiduciary requirements change, there is the danger of the entire industry model also changing.

As Lenin asked, “What is to be done?” Jason Zweig, whom I regard as the Zen Philosopher King of financial columnists, wrote a piece in the WSJ on May 23, 2015 entitled “Lessons From A Buffett Believer.” It is a discussion about the annual meeting of Markel Corporation and the presentation given by its Chief Investment Officer, Tom Gayner. Gayner, an active manager, has compiled a wonderful long-term investment record. However, he also has a huge competitive advantage. Markel is a property and casualty company that consistently underwrites at a profitable combined ratio. Gayner is always (monthly) receiving additional capital to invest. He does not appear to trade his portfolio. So the investors in Markel have gotten a double compounding effect both at the level of the investment portfolio and at the corporation (book value growth). And it has happened in a tax-efficient manner and with an expense ratio in investing that Vanguard would be proud of in its index funds.

As Lenin asked, “What is to be done?” Jason Zweig, whom I regard as the Zen Philosopher King of financial columnists, wrote a piece in the WSJ on May 23, 2015 entitled “Lessons From A Buffett Believer.” It is a discussion about the annual meeting of Markel Corporation and the presentation given by its Chief Investment Officer, Tom Gayner. Gayner, an active manager, has compiled a wonderful long-term investment record. However, he also has a huge competitive advantage. Markel is a property and casualty company that consistently underwrites at a profitable combined ratio. Gayner is always (monthly) receiving additional capital to invest. He does not appear to trade his portfolio. So the investors in Markel have gotten a double compounding effect both at the level of the investment portfolio and at the corporation (book value growth). And it has happened in a tax-efficient manner and with an expense ratio in investing that Vanguard would be proud of in its index funds.