By Samuel Lee

Objective and strategy

AQR offers its absolute return equity strategy in two mutual fund flavors: AQR Equity Market Neutral and AQR Long-Short Equity. Equity Market Neutral, or EMN, goes long global stocks that score well on proprietary composite measures and shorts global stocks that score poorly. AQR groups these measures into six broad “themes”:

- Value is the strategy of buying stocks that are cheap on fundamental measures such as book value, earnings, dividends and cash flow.

- Momentum is the strategy of buying stocks with strong recent relative performance according to measures such as price returns, abnormal returns after earnings announcements (earnings surprises), abnormal risk-adjusted returns (residual momentum), and returns of economically linked firms (indirect momentum).

- Earnings quality is the strategy of buying stocks with reported earnings that are more reliable indicators of future earnings, according to measures such as accruals.

- Stability is the strategy of buying stocks with defensive characteristics, such as low volatility, low beta, and low leverage.

- Investor sentiment is the strategy of buying stocks with wide agreement by “smart money”, according to measures such as low short interest as a percentage of market capitalization and high commonality of holdings by elite hedge funds.

- Management signaling is the strategy of buying stocks where management engages in actions that indicate financial strength or cheapness, such as debt retirement and share repurchases.

Stocks are ranked by these measures within each industry. The stocks with the highest composite scores are bought and the stocks with the lowest composite scores are shorted. Industry neutrality improves risk-adjusted returns on a wide variety of stock selection signals, perhaps because it removes persistent industry bets.

In addition, the strategy engages in country-industry pairs selection using the same six sets of signals and industry selection using only value and momentum. Because AQR dislikes concentrated bets, the country-industry pairs and industry selection strategies are allotted a smaller portion of the strategy’s overall risk than the stock-selection strategy.

The balance of the long and short sleeves is managed to produce returns uncorrelated with the MSCI World Index, a market-weighted benchmark of developed market stocks. This does not mean each sleeve has the same notional size. The long sleeve tends to exhibit lower volatility for each unit of notional exposure than the short sleeve. In order to balance them, the strategy must own more dollars of the long sleeve, creating the impression that it has net long equity exposure. The gross exposure for each sleeve has a floor of 100% NAV and a cap of 250% NAV, meaning the strategy’s gross exposure can range from 2x to 5x the net asset value of the fund. As of February end, AQR Equity Market Neutral had 190% notional long exposure and 173% notional short exposure, for a total gross notional exposure of 363%.

AQR takes steps to mitigate the risks of leverage. First, the strategy is well diversified, with over 1700 stock positions, most of them under 0.5% notional exposure and the biggest at a little under 1.7%. Single-stock concentration goes against every bone in AQR. Like most quant investors, AQR goes for seconds and thirds when it comes to the “free lunch” of diversification.

Second, AQR has a 6% annualized volatility target for the strategy, which means AQR will likely reduce gross leverage if its positions behave erratically. This is a trend-following strategy as periods of high volatility usually coincide with bad returns. For reference, the volatility target is about a third of the historical volatility of the U.S. stock market and roughly the same as the historical volatility of the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index (though in recent years the bond index’s volatility has dropped to about 3%).

Finally, the strategy applies what AQR calls a “drawdown control system”, a methodology for cutting risk when the strategy loses money and adding it back as it recoups its losses (or enough time lapses since a drawdown). The drawdown control system can cut the fund’s target volatility by up to half in the worst circumstances. AQR’s use of volatility targeting and drawdown control are common practices among quantitative investors. As a group these investors tend to cut and add risks at the same time. It is unclear whether they are influential enough to alter the nature of markets and perhaps render these methods obsolete or even harmful (think of portfolio insurance and its contribution to Black Monday in 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 22.6%). My guess is quantitative investors aren’t yet big enough because many more investors are counter-cyclical rebalancers over the short-run, particularly institutions. This is speculation, of course. The market is a big and wild herd that will sometimes stampede in a direction it had never gone before—a lesson AQR itself learned at least twice: during the madness of the dot-com bubble and during the great quant meltdown of 2007.

—

Long-Short Equity, or LSE, takes the EMN strategy (though they’re not exact clones if we’re to judge by their holdings and position sizes) and overlays a tactical equity strategy that targets an average 50% exposure to the MSCI World Index, with the ability to adjust its exposure by +/- 20% based largely on valuation and momentum. The equity exposure is obtained through futures.

In a back-test of a simplified version of the strategy, the market-timing component did not add much to the strategy’s performance while it worsened the drawdown during the financial crisis.

Adviser

AQR Capital Management, LLC, was founded in 1998 by a team of ex-Goldman Sachs quant investors led by Clifford S. Asness, David G. Kabiller, Robert J. Krail, and John M. Liew. (Krail is no longer with the firm.) AQR stands for Applied Quantitative Research. Asness, Krail and Liew met each other at the University of Chicago’s finance PhD program. The firm’s bread and butter has long been trading value and momentum together, an idea Asness studied in his dissertation under Eugene Fama, father of modern finance and one of the co-formulators of the efficient market hypothesis.

AQR is mostly owned by AQR Group LP, which in turn is owned by employees of the firm. AMG, a publicly traded asset manager, has owned a stake in AQR since 2004 and in 2014 it increased it, but remains a minority shareholder (terms of both transactions have not been disclosed). AMG largely leaves its investees to run themselves, so I am not concerned about the firm pushing AQR to do stupid things to meet or beat a quarterly target. Though the implosion of Third Avenue, an investee, may spur AMG to more actively monitor its portfolio companies, I doubt Asness and his partners gave AMG much power to meddle in AQR’s affairs.

AQR’s mutual fund business has grown rapidly in size and sophistication since 2009, when it launched arbitrage and equity momentum funds. It competes with DFA for the mantle of academic “thought leadership” among advisors, its main clients. This has put Asness in the awkward position of competing with his former mentor Fama, who is a significant shareholder in DFA and the chief intellectual architect of its approach. Like DFA, AQR emphasizes the primacy of factors in managing portfolios.

—

When AQR started up, it was hot. It had one of the biggest launches of any hedge-fund up to that point. Then the dot-com bubble inflated. The widening gap in valuations between value and growth stocks almost sunk AQR. According to Asness, had the bubble lasted six more months, he would have been out of business. When the bubble burst, the firm’s returns soared and so did its assets. The good times rolled on and the firm was on the verge of an IPO by late 2007. According to the New York Post, AQR had to shelve it as the subprime crisis began roiling the markets. The financial crisis shredded its returns, with its flagship Absolute Return fund falling more than 50 percent from the start of 2007 to the end of 2008. Firm-wide assets from peak-to-trough went from $39.1 billion to $17.2 billion. The good times are back: As of December-end, AQR had $142.2 billion in net assets under management.

The two near-death experiences have instilled in AQR a fear of concentrated business risks. In 2009, AQR began to diversify away from its flighty institutional clientele by launching mutual funds to entice stickier retail investors. The firm has also launched new strategies at a steady clip, including managed futures, risk parity, and global macro.

AQR has a strong academic bent. Its leadership is sprinkled with economics and finance PhDs from top universities, particularly the University of Chicago. The firm has poached academics with strong publishing records, including Andrea Frazzini, Lasse Pedersen, and Tobias Moskowitz. Its researchers and leaders are still active in publishing papers.

The firm’s principals are critical of hedge funds that charge high fees on strategies that are largely replicable. AQR’s business model is to offer up simplified quant versions of these strategies and charge relatively low fees.

Managers

Both the Equity Market Neutral and Long-Short Equity strategies are run by Jacques A. Friedman, Andrea Frazzini, and Michele L. Aghassi. Ronen Israel helps manage EMN. Hoon Kim helps manage LSE. All five are principals, or partners, in the firm.

Friedman heads AQR’s Global Stock Selection team. Prior to joining AQR at its inception in 1998, he developed quantitative stock selection strategies at Goldman Sachs. He is the principal portfolio manager and supervises Frazzini, Aghassi and Kim.

Israel heads AQR’s Global Alternative Premia Group. Prior to joining AQR in 1999, he was a senior analyst at Quantitative Financial Strategies, Inc.

Frazzini researches global stock-selection strategies. Prior to joining AQR in 2008 he was a star finance professor at the University of Chicago.

Aghassi is co-head of research of AQR’s Global Stock Selection team. Prior to joining AQR in 2005, she obtained her PhD in operations research at MIT.

Kim is the head of equity portfolio management in AQR’s Global Stock Selection team. Prior to joining AQR in 2005, he was head of quantitative equity research at Mellon Capital Management.

Israel and Friedman have master’s degrees in mathematics. Frazzini, Aghassi and Kim have PhDs.

Strategy capacity and closure

The EMN and LSE funds together have over $1.6 billion in assets. However, AQR runs hedge funds, institutional separate accounts, and foreign funds, and re-uses the same signals in different formats, such as long-only funds. The effective dollars dedicated to the signals use by the funds are almost certainly much higher than reported by the aggregate net asset values of the mutual funds.

Fortunately, AQR has a history of closing funds and ensuring its assets don’t overwhelm the capacity of its strategies. When the firm launched in 1998, it could have started with $2 billion but chose to manage only half that, according to founding partner David Kabiller. Of its mutual funds, AQR has already closed its Multi-Strategy Alternative, Diversified Arbitrage and Risk Parity mutual funds. Soon after I wrote about AQR Style Premia Alternative QSPIX and AQR Style Premia LV QSLIX in the September 2015 edition of MFO, AQR announced a soft close of the funds. It went into effect on March 31, 2016. AQR will meet additional demand by launching funds that are tweaked to have more capacity.

Management’s stake in the funds

As of December 31, 2014, the funds’ managers had relatively low investments in the mutual funds.

- Friedman had $50,001 to $100,000 in the EMN fund and $100,001 to $500,000 in the LSE fund.

- Israel had no investment in the EMN fund.

- Frazzini had $10,001 to $50,000 in both funds.

- Aghassi had no investments in either fund.

- Kim had no investment in the LSE fund.

The low levels of investment should not be held against the managers. It is cheaper and more tax efficient for them to invest in the strategies through AQR’s hedge funds. They also have a direct interest in the success of the firm. Unlike many other hedge funds, AQR does not compensate partners and employees largely based on the profits attributable to them. The team-based nature of AQR’s quantitative process means profits cannot be cleanly attributable to a given employee. Moreover, there is a huge element of luck in the performance of a given strategy and AQR rightly does not want to overwhelmingly tie compensation to it. All the portfolio managers of the funds are partners and so earn a payout based on the firm’s earnings and their relative ownership stakes. AQR grants ownership stakes based on “cumulative research, leadership and other contributions.”

I expect that over time the managers’ stakes will rise as a matter of window-dressing for consultants who take a check-the-box approach to due diligence (most of them). There is evidence that window-dressing has occurred: Some of AQR’s principals own both the low- and high-volatility versions of the same strategy, which is strange because it is costlier to own the low-volatility version per unit of exposure.

Opening date

AQR Long-Short Equity started on July 16, 2013. AQR Equity Market Neutral started on October 7, 2014. AQR has been running long-short stock-selection strategies since its 1998 founding.

Minimum investment

$1 million for the N shares, $5 million for the I shares. The minimums are waived at certain brokerages. Fidelity, for example, allows investments as small as $2500 in IRAs. Fee-only financial advisors have no investment minimums.

Expense ratio

QMNIX shares are 1.50% with $208 million in assets and QLEIX shares are 1.36% with $597 million in assets, as of June 2023.

Comments

Both funds have been closed to new investors as of 2017.

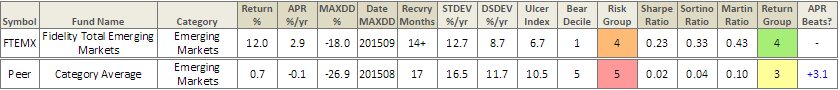

Since its October 2014 inception, AQR Equity Market Neutral Fund I QMNIX has returned 18.6% annualized with a standard deviation of 7.0%, for a Sharpe ratio of 2.66. Since its July 2013 inception, AQR Long-Short Equity Fund I QLEIX has returned 14.4% above its benchmark (a 50-50 blend of the MSCI World Index and cash) with a standard deviation of 5.8%, for a Sharpe ratio of 2.46. Almost all of the abnormal returns were driven by the market-neutral equity stock selection sleeve; AQR’s tactical market timing in the LSE strategy contributed zilch to the fund’s returns from inception to the end of 2015.

These are not sustainable numbers. A more reasonable, conservative long-run Sharpe ratio is 0.5. Translated to a raw return, that’s 3% above cash for a market-neutral strategy that runs at a 6% volatility.

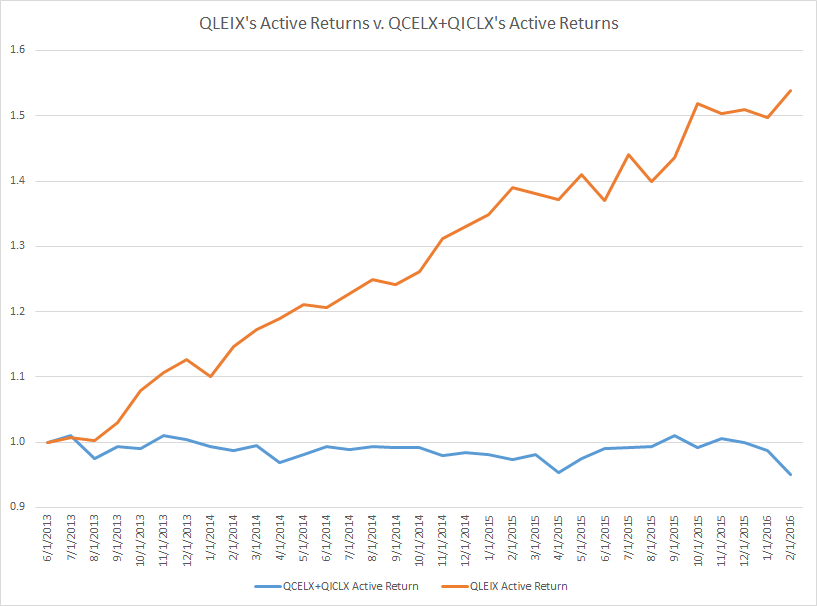

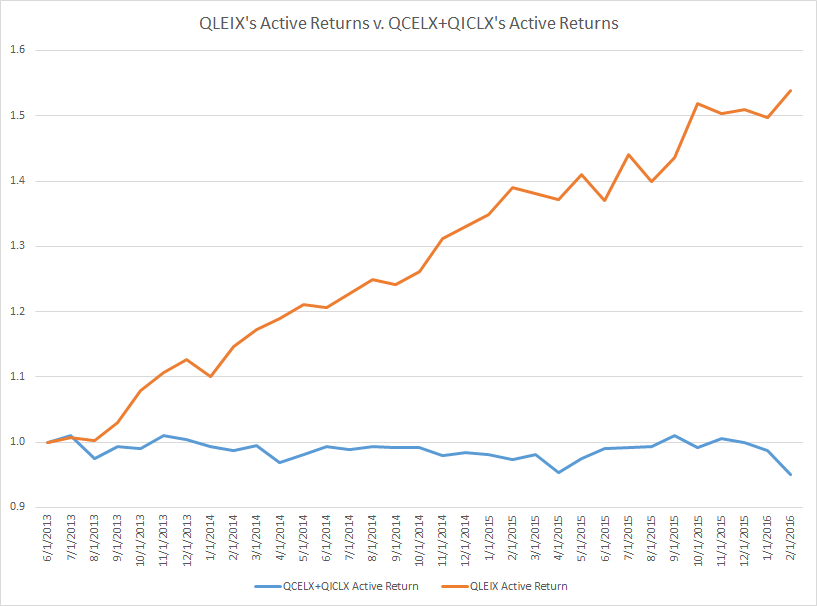

While AQR’s absolute return global stock selection strategy has done well, its long-only funds have not. Since the LSE fund launched in 2013, its active returns (that is, returns above its benchmark) have far outstripped the active returns of the AQR Multi-Style funds. In the chart below I plotted the cumulative active returns of AQR Long-Short Equity (which has a longer live track record than AQR Equity Market Neutral) against a sum of the active returns of AQR Large Cap Multi-Style I QCELX and AQR International Multi-Style I QICLX. The long-only funds have stagnated, while the long-short fund has consistently made lots of money. While I doubt this divergence will remain big and persistent, I’m confident that it’s well worth paying up for AQR’s long-short strategy.

Bottom line

AQR’s long-short global stock-selection strategy is well worth the money and a better deal than its long-only stock funds.

Fund Website

AQR Equity Market Neutral

AQR Long-Short Equity

Sam Lee and Severian Asset Management

Sam Lee and Severian Asset Management

Sam is the founder of Severian Asset Management, Chicago. He is also former Morningstar analyst and editor of their ETF Investor newsletter. Sam has been celebrated as one of the country’s best financial writers (Morgan Housel: “Really smart takes on ETFs, with an occasional killer piece about general investment wisdom”) and as Morningstar’s best analyst and one of their best writers (John Coumarianos: “ Lee has written two excellent pieces [in the span of a month], and his showing himself to be Morningstar’s finest analyst”). He has been quoted by The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Financial Advisor, MarketWatch, Barron’s, and other financial publications.

Severian works with high net-worth partners, but very selectively. “We are organized to minimize conflicts of interest; our only business is providing investment advice and our only source of income is our client fees. We deal with a select clientele we like and admire. Because of our unusual mode of operation, we work hard to figure out whether a potential client, like you, is a mutual fit. The adviser-client relationship we want demands a high level of mutual admiration and trust. We would never want to go into business with someone just for his money, just as we would never marry someone for money—the heartache isn’t worth it.” Sam works from an understanding of his partners’ needs to craft a series of recommendations that might range from the need for better cybersecurity or lower-rate credit cards to portfolio reconstruction.

[cr2016]

Sam Lee and

Sam Lee and