At the time of publication, this fund was named Janus Global Unconstrained Bond Fund.

Objective and strategy

The fund is seeking maximum total return, consistent with preservation of capital. Consistent with its name, the manager is free to invest in virtually any income-producing security; the prospectus lists corporate and government bonds, both international and domestic, convertibles, preferred stocks, common stocks “which have the potential for paying dividends” and a wide variety of derivatives. Up to 50% of the portfolio may be invested in emerging markets. The manager can lend, presumably to short-sellers, up to one-third of the portfolio. The duration might range from negative three years, a position in which the portfolio would rise if interest rates rose, to eight years.

Adviser

Janus Capital Management, LLC. Janus is a Denver-based investment advisor that manages $178 billion in assets. $103 billion of those assets are in mutual funds. Janus was made famous by the success of its gun-slinging equity funds in the 1990s and infamous by the failure of its gun-slinging equity funds in the decade that followed. It made headlines for management turmoil, involvement in a market-timing scandal, manager departures and lawsuits. Janus advises 54 Janus, Janus Aspen, INTECH and Perkins mutual funds; of those, 28 have managers with three years or less on the job.

Manager

William Gross. Mr. Gross founded PIMCO, as well as serving as a managing director, portfolio manager and chief investment officer for them. Morningstar recognized him as its fixed income manager of the decade for 2000-09 and has named him as fixed-income manager of the year on three occasions. His media handle was “The Bond King,” a term which Google finds associated with his name on 100,000 occasions. He was generally recognized as one of the industry’s three most accomplished fixed-income investors, along with Jeffrey Gundlach of DoubleLine and Dan Fuss of Loomis Sayles. At the time of his departure from PIMCO, he was responsible for $1.8 trillion in assets and managed or co-managed 34 mutual funds.

Strategy capacity and closure

Not yet reported. PIMCO allowed its Unconstrained Bond fund, which Mr. Gross managed in 2014, to remain open after assets reached $20 billion. That fund has trailed two-thirds or more its “non-traditional bond” peers for the past one- , three- and five-year periods.

Active share

Not available.

Management’s stake in the fund

Not yet recorded. Mr. Gross reputedly had $240 million invested in various PIMCO funds and might be expected to shift a noticeable fraction of those investments here but there’s been no public statement on the matter.

Opening date

May 27, 2014.

Minimum investment

$2,500 for “A” shares and no-load “T” shares. There are, in whole, seven share classes. Brokerage availability is limited, a condition which seems likely to change.

Expense ratio

The fund has 8 different share class with expense ratios ranging from 0.63% to 1.71% and assets under management of $58.7 million, as of July 2023.

Comments

The question isn’t whether this fund will draw billions of dollars. It will. Mr. Gross, a billionaire, has a personal investment in the PIMCO funds reportedly worth $250 million. I expect much will migrate here. He’s been worshipped by institutional investors and sovereign wealth fund managers. Thousands of financial advisors will see the immediate opportunity to “add value” by “moving ahead of the crowd.” The Wall Street Journal reported that PIMCO saw $10 billion in asset outflows at the announcement of Mr. Gross’s departure (“Pimco’s New CIOs: ‘Bill Gross Relied on Us,’” 9/29/14) and speculated that outflows could reach $100 billion.

No, the question isn’t whether this fund attracts money. It’s whether the fund should attract your money.

Three factors would predispose me against such an investment.

-

Mr. Gross’s reported behavior does not inspire confidence. Mr. Gross’s departure from PIMCO was not occasioned by poor performance; it was occasioned by poor behavior. The evidence available suggests that he has become increasingly autocratic, irascible, disrespectful and inconsistent. The record of PIMCO’s loss of talented staff – both those who left because they could not tolerate Mr. Gross’s behavior and those who apparently threatened to resign en masse over it – speaks to a sustained, substantial problem. Josh Brown of Ritzholz Wealth Management suspects that Gross’s dramatically wrong market bets led him “to hunker down. To throw people out of one’s office when they voice dissension. To view the movement of the market as an affront to one’s intelligence … for a highly-visible professional investor [such a mindset] becomes utterly debilitating.” We’ve wondered, especially after the Morningstar presentation, whether there might be a health issue somewhere in the background. Regardless of its source, the behavior is an unresolved problem.

-

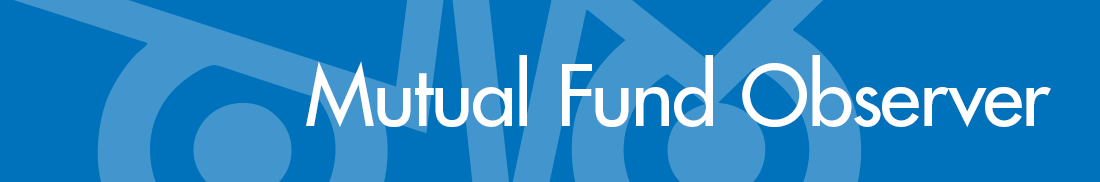

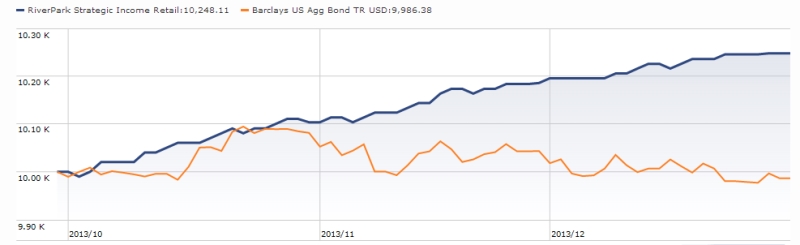

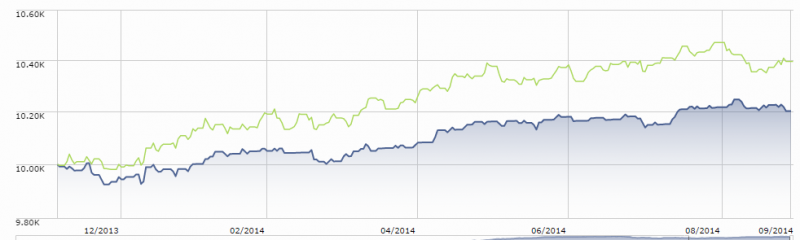

Mr. Gross’s recent performance does not inspire confidence. Not to put too fine a point on it, but Mr. Gross already served as manager of an unconstrained bond portfolio, PIMCO Unconstrained Bond and its near-clone Harbor Unconstrained Bond, and his performance was distinctly mediocre. He assumed control of the fund in December 2013 when Chris Dialynis took a sudden sabbatical which some now attribute to fallout from an internal power struggle. Regardless of the motive, Mr. Gross assumed control and trailed his peers (the green line) through the year.

While the record is too short to sustain much of a judgment, it does highlight the fact that Mr. Gross does not arrive bearing a magic wand.

-

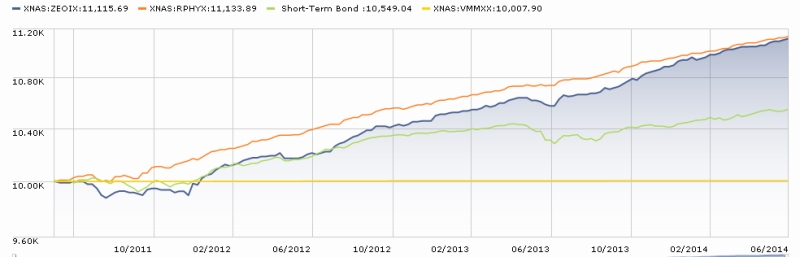

Mr. Gross is apt to feel that he’s got something to prove. It is hard to imagine that he does not approach this new assignment with a considerable chip on his shoulder. He has always had a penchant for bold moves, some of which have substantially damaged his shareholders. Outsized bets in favor of TIPs and emerging markets bonds (2013) and against Treasuries (2011) are typical of the “Macro bets [that] have come to dominate the fund’s high-level decision-making in recent years” (Morningstar analyst Eric Jacobson, July 16 2013). The combination of a tendency to make bold bets and the unavoidable pressure to show the world they were wrong is fundamentally troubling.

Bottom Line

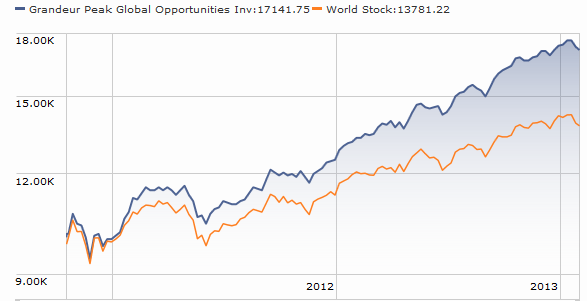

Based on Mr. Gross’s long track record with PIMCO Total Return, you might be hoping for returns that exceed their benchmark by 1-2% per year. Over the course of decades, those gains would compound mightily but Mr. Gross, 70, will not be managing this fund for decades. The question is, what risk are you assuming in pursuit of those very modest gains over the relatively modest period in which he’s likely to run the fund? Shorn of his vast analyst corps and his place on the world stage, the answer is not clear. As a general rule, in the most conservative part of your portfolio, clarity on such matters would be deeply desirable. We’d counsel watchful waiting, the fund is likely to still be available in six months and the picture will be far clearer then.

Fund website

Janus Henderson Absolute Return Income Opportunities Fund

[cr2014]