At the time of publication, this fund was named Advisory Research Strategic Income.

Objective and Strategy

The fund seeks high current income and, as a secondary objective, long term capital appreciation. It invests primarily in straight, convertible and hybrid preferred securities but has the freedom to invest in other income-producing assets including common stock. The advisor wants to achieve “significantly higher yields” than available through Treasury securities while maintaining an investment-grade portfolio. That said, the fund may invest “to a limited extent” in high-yield bonds, may invest up to 20% in foreign issues and may write covered call options against its holdings. Morningstar categorizes it as a Long-Term Bond fund, which is sure to generate misleading peer group performance stats since it’s not a long-term bond fund.

Adviser

Advisory Research (ARI). AR is a Chicago-based advisor for some of the nation’s wealthiest individuals, as well as privately-held companies, endowments, foundations, pensions and profit-sharing plans. They manage over $10.0 billion in total assets and advise the five AR funds.

Manager

Brien O’Brien, James Langer and Bruce Zessar. Mr. O’Brien is ARI’s CEO. He has 34 years of investment experience including stints with Marquette Capital, Bear Stearns and Oppenheimer. He graduated with honors from Boston College with a B.S. in finance and theology. He oversees four other AR funds. Mr. Langer is a Managing Director and helps oversee two other AR funds. Like Mr. O’Brien, he worked for Marquette Associates. His career started at the well-respected Center for Research in Security Prices at the University of Chicago. Mr. Zessar has a J.D. from Stanford Law and 11 years of investing experience. Mr. Zessar also co-manages All-Cap Value (ADVGX). The team manages about $6 billion in other accounts.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

Mr. O’Brien provided a seed investment when the strategy was launched in 2003, and today has over $1 million in the fund. Mr. Langer has around a half million in the fund and Mr. Zessar had between $10,000 and $50,000 in the fund.

Strategy capacity and closure

They estimate a strategy capacity of about $1 billion; since they do invest heavily in preferred shares but have the ability to invest elsewhere, they view the cap as flexible. Mr. Zessar notes that the few others open-end funds specializing in preferred shares have asset bases of $1 – 5 billion.

Opening date

December 31, 2012 after the conversion of one limited partnership account, Advisory Research Value Income Fund, L.P., which commenced operations on June 30, 2003 and the merger of another.

Minimum investment

$2500.

Expense ratio

0.90%, after waivers, on assets of $167.9 million, as of July 2023. 1.15%, after waivers, for “A” class shares.

Comments

Preferred stocks are odd creatures, at least in the eyes of many investors. To just say “they are securities with some characteristics of a bond and some of a stock” is correct, but woefully inadequate. In general, preferred stock carries a ticker symbol and trades on an exchange, like common stock does. In general, preferred stockholders have a greater claim on a firm’s dividend stream than do common stockholders: preferred dividends are paid before a company decides whether it can pay its common shareholders, tend to be higher and are often fixed, like the coupon on a bond.

But preferred shares have little potential for capital appreciation; they’re generally issued at $25 and improving fortunes of the issuing firm don’t translate to a rising share price. A preferred stock may or may not have maturity like a bond; some are “perpetual” and many have 30-40 year maturities. It can either pay a dividend or interest, usually quarterly or semi-annually. Its payments might be taxed at the dividend rate or at your marginal income rate, depending. Some preferred shares start with a fixed coupon payment for, say, ten years and then exchange it for a floating payment fixed to some benchmark. Some are callable, some are not. Some are convertible, some are not.

As a result of this complexity, preferred shares tend to be underfollowed and lightly used in open-end funds. Of the 7500 extant open-end mutual funds, only four specialize in preferred securities: ADVNX and three load-bearing funds. A far larger number of closed-end funds invest in these securities, often with an overlay of leverage.

What’s the case for investing in preferred stocks?

Steady income. Strategic Income’s portfolio has a yield of 4.69%. By comparison, Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury Fund (VFITX) has a 30-day yield of 1.38% and its broader Intermediate-Term Bond Index Fund (VBIIX) yields 2.64%.

The yield spread between the fed funds rate and the 10-year Treasury is abnormally large at the moment (about 280 bps in late August); when that spread reverts to its normal level (about 150 bps), there’s also the potential for a little capital appreciation in the Strategic Income fund.

In the long term, the managers believe that they will be able to offer a yield of about 200-250 basis points above what you could get from the benchmark 10-year Treasury. At the same time, they believe that they can do so with less interest rate sensitivity; the fund has, in the past, shown the interest rate sensitivity associated with a bond portfolio that has a six or seven year maturity.

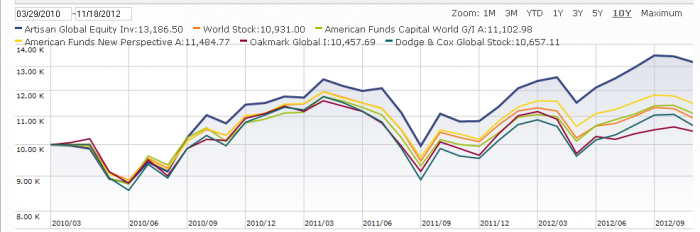

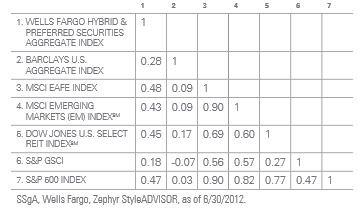

In addition, preferred stocks have traditionally had low correlations to other asset classes. A 2012 report from State Street Global Advisors, The Case for Preferred Stocks, likes the correlation between preferred shares and bonds, international stocks, emerging markets stocks, real estate, commodities and domestic common stocks for the 10 years from 2003 to 2012:

As a result, adding preferred stock to a portfolio might both decrease its volatility and its interest rate sensitivity while boosting its income.

What’s the case for investing with Advisory Research?

They have a lot of experience in actively managing this portfolio.

Advisory Research launched this fund’s predecessor in 2003. They converted it to a mutual fund at the end of 2012 in response to investor demands for daily liquidity and corrosive skepticism of LPs in the wake of the Madoff scandal. The existing partners voted unanimously for conversion to a mutual fund.

From inception through its conversion to a mutual fund, the L.P. returned 4.24% annually while its benchmark returned 2.44%, an exceptionally wide gap for a fixed-income fund. Because it’s weakly correlated to the overall stock market, it has held up relatively well in downturns, losing 25.8% in 2008 when the S&P 500 dropped 37%. The fund’s 28.1% gain in 2009 exceeded the S&P’s 26.5% rebound. It’s also worth noting that the same management team has been in place since 2003.

The team actively manages the portfolio for both sector allocation and duration. They have considerable autonomy in allocating the portfolio, and look to shift resources in the direction of finding “safe spread.” That is, for those investments whose higher yield is not swamped by higher risk. In mid-2012, 60% of the portfolio was allocated to fixed preferred shares. In mid-2013, they were half that. The portfolio instead has 50% in short-term corporate bonds and fixed-to-floating rate securities. At the same time, they moved aggressively to limit interest-rate risk by dramatically shortening the portfolio’s duration.

Bottom Line

This is not a riskless strategy. Market panics can drive even fundamentally sound securities lower. But panics are short-term events. The challenge facing conservative investors, especially, is long-term: they need to ask the question, “where, in the next decade or so, am I going to find a reasonable stream of income?” With the end of the 30-year bond bull market, the answer has to be “in strategies that you’ve not considered before, led by managers whose record is solid and whose interests are aligned with yours.” With long-term volatility akin to an intermediate-term corporate bond fund’s, substantial yield, and a stable, talented management team, Advisory Research Strategic Income offers the prospect of a valuable complement to a traditional bond-centered portfolio.

Fund website

North Square Strategic Income. SSgA’s The Case for Preferred Stock (2012) is also worth reading, recalling that ADVNX’s portfolio is neither all-preferred nor locked into its current preferred allocation.

SSgA’s Preferred Securities 101

[cr2013]