By David Snowball

Dear friends,

Sorry about the late launch of the Observer, but we’ve been consumed by the need to deal with a campus crime.

Someone stole the dome off my academic home, Old Main, early on the morning of April 1st.

The barstids!

If you play the accompanying video (probably best with the sound muted), there are some way cool images of the pre-theft dome which occur around the: 45 second mark. It’s accompanied by some commentary by a couple of my students and my colleague, Wendy, who, like Anakin, has heard the song of the Dark Side.

Requiem for a heavyweight

The sad tale of Sequoia’s (SEQUX) unwinding continues.

Here’s the brief version of recent events:

Here’s the brief version of recent events:

- Investors have pulled more than a half billion from the fund, including $230 million just in the first three weeks of March. March will be the sixth consecutive month of net withdrawals.

- The fund trails 98-100% of its peers for 2015 and 2016, as well as for the past one- and three-year periods.

- Manager Bob Goldfarb, whose name is on the door at Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb, resigned and an unnamed analyst who was one of the cheerleaders for Valeant left.

- The remaining guys have had a period of reflection and propose a more collaborative decision-making model and less risk-taking for the years ahead.

|

Senator Arthur Vandenberg (served 1928-1951), a Republican committed to the critical importance of a united front when it came to foreign policy, famously declared “politics stops at the water’s edge.” The fear is that the Sequoia version might have been “independence stops at the boss’s door.”

|

The dark version of the Sequoia narrative would be this: Goldfarb, abetted by an analyst, became obsessed about Valeant and crushed any internal dissent. Mr. Poppe, nominally Mr. Goldfarb’s peer, wouldn’t or couldn’t stop the disaster. “All the directors had repeatedly expressed concern” over the size of the Valeant stake and the decision to double-down on it. Mr. Poppe dismissed their concerns: “recent events frustrated them.” The subsequent resignations by 40% of the board, with another apparently threatening to go, were inconsequential annoyances. Sequoia, rather snippily, noted that board members don’t control the portfolio, the managers do. Foot firmly on the gas, they turned the bus toward the cliff.

If the dark version is right, Jaffe is wrong. The headline on a recent Chuck Jaffe piece trumpeted “How a big bet on one bad stock broke a legendary mutual fund” (3/28/2016). If the dark narrative is right, “One bad stock” did not break Sequoia; an arrogant and profoundly dysfunctional management culture did.

|

Do you seriously think that you’d be braver? In the wake of Josef Stalin’s death, Nicolas Khrushchev gave a secret speech denouncing the horrors of Stalin’s reign and his betrayal of the nation. Daniel Schorr picks up the narrative:

It was said that at one point a delegate shouted, “And Nikita Sergeyevich, where were you while all this was happening?” Khrushchev had looked up and snapped, “Who said that? Stand up!” When no one rose, Khrushchev said, “That’s where I was, comrade” (from Daniel Schorr, Stay Tuned (2001), 75-76).

|

Another version, though, starts with this question: “did Goldfarb fall on his sword?” His entire professional life has been entwined with Sequoia, the last living heir to the (Bill) Ruane, (Richard) Cunniff and Goldfarb legacy. Ruane and Cunniff started the firm in 1970, Goldfarb joined the next year and has spent 45 years at it. And now it was all threatening to come apart. Regardless of “who” or “why,” some dramatic gesture was called for. If the choice came down to Goldfarb, age 71, or Poppe, at 51 or 52, it was fairly clear who needed to draw his gladius.

Meanwhile, the usual suspects rushed to close the barn door.

-

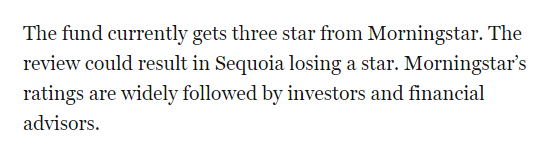

Morningstar reduced the fund’s Analyst Rating from Gold to Bronze. Why? In the same way that a chef might be embarrassed to celebrate the tender delights of a fish flopping around on the ground, Morningstar’s analysts might have been embarrassed to look at an operation whose wheels were coming off and declaring it “the best of the best.”

Oddly, they also placed it “under review” on October 30, 2015. At that point, Valeant was over 30% of the fund, investors had been pulling money and the management team conducted their second, slightly-freakish public defense of their Valeant stake. Following the review, the analysts reaffirmed their traditional judgment: Gold! The described it as “compelling” in the week before the review and “a top choice” in the week afterward.

There’s no evidence in the reaffirmation statement that the analysts actually talked to Sequoia management. If they didn’t, they were irresponsible. If they did and asked about risk management, they were either deceived by management (“don’t worry, we’re clear-eyed value investors and we’re acting to control risk”) or management was honest (“we’re riding out the storm”) and the analysts thought “good enough for us!” I don’t find any of that reassuring.

Doubts have only set in now that the guys presumably responsible for the mess are gone and the management strategy is becoming collaborative and risk-conscious.

Similarly, up until quite recently Morningstar’s stock analyst assigned to Valeant recognized “near-term pain” while praising the firms “flawless execution” of its acquisition strategy and the “opportunities [that] exist for Valeant long term.”

- Steve Goldberg, an investment advisor who writes for Kiplinger’s, “still had faith in the fund” back in October after the board members resigned and the extent of the Valeant malignancy was clear. But “What I didn’t know: Valeant was no Berkshire Hathaway.” (stunned silence) Uh, Steve, maybe you should let someone else hold the debit card, just to be safe? Mr. Goldberg correctly points out that Bill Nygren, manager of Oakmark Select (OAKLX), stubbornly rode his vast holdings in Washington Mutual all the way to zero. The lesson he’s learned, curiously late in his professional investing career, “I need to make sure a fund isn’t taking excessively large positions in one or two stocks or engaging in some other dicey strategy. Dramatically outsize returns almost never come without outsize risks.”

The excuse “we couldn’t have known” simply does not hold water. A pseudonymous contributor to Seeking Alpha, who describes himself only as “an engineer in Silicon Valley” wrote a remarkably prescient, widely ignored critique of Sequoia two years ago. After attending Sequoia’s Investor Day, he came away with the eerie sense that Rory Priday and Bob Goldfarb spoke most. The essay makes three prescient claims: that Valeant hadn’t demonstrated any organic growth in years, that they’d been cooking the books for years, and that Goldfarb and Priday were careless in their statements, inexperienced in pharma investing and already hostage to their Valeant stake.

Valeant’s largest shareholder, [Sequoia’s] fate has become inextricably intertwined with Valeant. Valeant is 23% of their portfolio and they own 10% of Valeant. They can’t exit without ruining their returns. This led to a highly desperate defense at the Ruane, Cunniff, Goldfarb annual meeting.

If an amateur investor could smell the rot, why was it so hard for professionals to? The answer is, we blind ourselves by knowing our answers in advance. If I start with the conclusion, “you can’t do much better than the legendary Sequoia,” then I’ll be blind, deaf and dumb on their behalf for as long as I possibly can be.

The bottom line: start by understanding the risks you’re subjecting yourself to. We ignore risks when times are good, overreact when times are bad and end up burned at both ends. If you can’t find your manager’s discussion of risk anywhere except in the SEC-mandated disclosure, run away! If you do find your manager’s discussion of risk and it feels flippant or jaded (“all investing entails risk”), run away! If it feels incomplete, call and ask questions of the advisors. (Yes, people will answer your questions. Trust me on this one.) If, at the end of it all, you’re thinking, “yeah, that makes sense” then double-check your understanding by explaining the risks you’re taking to someone else. Really. Another human being. One who isn’t you. In my academic department, our mantra is “you haven’t really learned something until you’ve proven you can teach it to someone else.” So give yourself that challenge.

Quick note to Fortune: Help staff get the basics right

In Jen Wieczner’s March 18, 2016 story for Fortune, she warns “Sequoia Fund, a mutual fund once renowned for its stock-picking prowess, has been placed under review by Morningstar.” The stakes are high:

Uhh, no. Morningstar is not Michelin. Their stars are awarded based on a mathematical model, not an analyst’s opinions (“This Valeant investor is in even bigger trouble than Bill Ackman,” Fortune.com. The error was corrected eventually).

The Honorable Thing

“Advertising is the modern substitute for argument; its function is to make the worse appear the better.”

“Advertising is the modern substitute for argument; its function is to make the worse appear the better.”

George Santayana

So we find one chapter at Sequoia Fund coming to a close, and the next one about to begin. On this subject my colleague David has more to offer. I will limit myself to saying that it was appropriate, and, the right thing to do, for Bob Goldfarb to elect to retire. After all, it happened on his watch. Whether or not he was solely to blame for Valeant, we will leave to the others to sort out in the future. Given the litigation which is sure to follow, there will be more disclosures down the road.

A different question but in line with Mr. Santayana’s observations above, is, do those responsible for portfolio miscues, always do the honorable thing? When one looks at some of the investment debacles in recent years – Fannie and Freddie, Sears, St. Joe, Valeant (and not just at Sequoia), Tyco, and of course, Washington Mutual (a serial mistake by multiple firms) – have the right people taken responsibility? Or, do the spin doctors and public relations mavens come in to do damage control? Absent litigation and/or whistle blower complaints, one suspects that there are fall guys and girls, and the perpetrators live on for another day. Simply put, it is all about protecting the franchise (or the goose that is laying the golden eggs) on both the sell side and the buy side. Probably the right analogy is the athlete who denies using performance enhancing drugs, protected, until confronted with irrefutable evidence (like pictures and test results).

Lessons Learned

Can the example of the Sequoia Fund be a teaching moment? Yes, painfully. I have long felt that the best way to invest for the long-term was with a concentrated equity portfolio (fewer than twenty securities) and some overweight positions within that concentration. Looking at the impact Sequoia has had on the retirement and pension funds invested in it, I have to revisit that assumption. I still believe that the best way to accumulate personal wealth is to invest for the long-term in a concentrated portfolio. But as one approaches or enters retirement, it would seem the prudent thing to do is to move retirement moneys into a very diverse portfolio or fund. That way you minimize the damage that a “torpedo” stock such as Valeant can do to one’s retirement investments, and thus to one’s standard of living, while still reaping the greater compounding effects of equities. There will still be of course, market risk. But one wants to lessen the impact of adverse security selection in a limited portfolio.

Remember, we tend to underestimate our life expectancy in retirement, and thus underweight our equity allocations relative to cash and bonds. And in a period such as we are in, the risk free rate of return from U.S. Treasuries is not 12% or 16% as it was in the early 1980’s (although it is perhaps higher than we think it is). And for that retirement equity position, what are the choices? Probably the easiest again, is something like the Vanguard Total Stock Market or the Vanguard S&P 500 index funds, with minimal expense ratios. We have been talking about this for some time now, but Sequoia provides a real life example of the adverse possibilities. And, it is worth noting that almost every concentrated investment fund has underperformed dramatically in recent years (although the reasons may have more to do with too much money chasing too few and the same good ideas). Is it really worth a hundred basis points to pay someone to own Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, as their top twenty holdings? Take a look sometime at the top twenty holdings of the largest actively managed funds in the respective categories of growth, growth and income, etc., and see what conclusions you draw.

The more difficult issue going forward will be deflation versus inflation. We have been in a deflationary world for some time now. It is increasingly apparent that the global central banks are in the process (desperately one suspects) to reflate their respective economies out of stagnant or no growth. Thus we see a variety of quantitative easing measures which tend to favor investors at the expense of savers. Should they succeed, it is unlikely that the inflation will stop at their targets (2% here), and the next crisis will be one of currency debasement. The more things change.

Gretchen Morgenson, Take Two

As should be obvious by now, I am a fan of Ms. Morgenson’s investigative reporting and her take no prisoners approach. I don’t know her from Adam, and could be standing next to her in the line for a bagel and coffee in New York and would not know it. But, she has a wonderful knack for goring many of the oxen that need to be gored.

In this Sunday’s New York Times Business Section, she raised the question of the effectiveness of share buybacks. Now, the dirty little secret for some time has been that growth of a business is not impacted by share repurchases. Yet, if you listened to many portfolio managers wax poetic about how they only invest with shareholder friendly managements (which in retrospect turn out to have not been not so shareholder friendly after they have been indicted by a grand jury). Share repurchase does increase per share metrics, such as book value and earnings. While the pie stays the same size, the size of the pieces changes. But often in recent years, one wonders why the number of shares outstanding does not change after a repurchase of what looked to have been 5% or so of shares outstanding during the year.

Well, that’s because management keeps awarding themselves options, which are approved by the board. And the options have the effect of selling the business incrementally to the managers over time, unless share purchases eliminate the dilution from issuing the options. Why approve the options packages? Well, the option packages are marketed to the share owners as critical to attracting and retaining good managers, AND, aligning the interests of management with the interests of shareholders. Which is where Mr. Santayana comes in – the bad (for shareholders) is made to look good with the right buzzwords.

However, I think there is another reason. Obviously growing a business is one of the most important things a management can do with shareholder capital. But today, every capital allocation move of reinvesting in a business for growth and expansion directly or by acquisition, faces a barrage of criticism. The comparison is always against the choices of dividends or share repurchase. I think the real reason is somewhat more mundane.

The quality of analysts on both the buy and sell side has been dumbed down to the point that they no longer know how to go out and evaluate the impact of an acquisition or other growth strategy. They are limited to running their spread sheet models against industry statistics that they pull off of their Bloomberg terminals. I remember the horror with which I was greeted when I suggested to an analyst that perhaps his understanding of a company and its business would improve if he would find out what bars near a company’s plants and headquarters were favorites of the company’s employees on a Friday after work and go sit there. Now actually I wasn’t serious about that (most of the analysts I knew lacked the social graces and skills to pull it off). I was serious about getting tickets to industry tradeshows and talking to the competitor salespeople at their booths. You would be amazed about how much you can learn about a company and its products that way. And people love to talk about what they do and how it stands up against their competition. That was a stratagem that fell on deaf ears because you actually had to spend real dollars (rather than commission dollars), and you had to spend time out of the office. Horrors! You might have to miss a few softball games.

The other part of this is managements and the boards, which also have become deficient at understanding the paths of growing and reinvesting in a business that was entrusted to them.

Sadly, what we have today is a mercenary class of professional managers who can and will flit from opportunity to opportunity, never really understanding (or loving) the business. And we also have a mercenary class of professional board members, who spend their post-management days running their own little business – a board portfolio. And if you doubt all of this, take a look again at Valeant and the people on the board and running the business. It was and is a world of consultants and financial engineers, reapplying the same case study or stratagem they had used many times before. The end result is often a hollowed-out shell of a company, looking good to appearances but rotting away on the inside.

By Edward Studzinski.

Steve Romick: A bit more faith is warranted

In our March issue, I reflected on developments surrounding three of the funds in which I’m invested: FPA Crescent (FPACX), my largest holding, Artisan Small Cap Value (ARTVX), my oldest holding, and Seafarer Overseas Growth & Income (SFGIX), my largest international holding. I wrote that two things worried me about FPA Crescent:

First, the fund has ballooned in size with no apparent effort at gatekeeping … Second, Romick blinked.

That is, the intro to his 2015 Annual Report appeared to duck responsibility for poor performance last year. My bottom line on FPA was “I’ve lost faith. I’m not sure whether FPA is now being driven by investment discipline, demands for ideological purity or a rising interest in gathering assets. Regardless, I’m going.”

Ryan Leggio, now a senior vice president and product specialist for FPA but also a guy who many of you would recall as a former Morningstar analyst, reached out on Mr. Romick’s behalf. There were, they believed, factors that my analysis hadn’t taken into account. The hope was that in talking through some of their decision-making, a fuller, fairer picture might emerge. That seemed both generous and thoughtful, so we agreed to talk.

On the question of Crescent’s size, Mr. Romick noted that he’d closed the fund before (from 2005-08) and would do so again if he thought that was necessary to protect his shareholders and preserve the ability to achieve their stated goal of equity-like rates of return with less risk than the market over the long-term. He does not believe that’s the case now. He made three points:

-

His investable universe has grown. That plays out in two ways: he’s now investing in securities that weren’t traditionally central to him and some of his core areas have grown dramatically. To illustrate the first point, historically, Mr. Romick purchased a security only if its potential upside was at least three times greater than its potential downside. He’s added to that an interest in compounders, stocks with the prospect of exceedingly consistent if unremarkable growth over time. Similarly, they continue to invest in mid-cap stocks, which are more liquid than small caps but respond to many of the same forces. Indeed, the correlation between the Vanguard Small Cap (NAESX) and Mid Cap (VIMSX) index funds soared after the late 1990s and is currently .96. At the same time, the number of securities in some asset classes has skyrocketed. In 2000, there was $330 billion in high-yield bonds; today that’s grown to $1.5 trillion. In an economic downturn, those securities can be very attractively priced very quickly.

-

His analytic and management resources have grown. For his first 15 years, Mr. Romick basically managed the fund alone. In recent years, as some of the long-time partners came toward the ends of their careers, FPA “reinvested in people in a very big way which has given me a very large, high capability team.” That culminated in the June 2013 appointment of two co-managers, Mark Landecker and Brian Selmo. Mr. Landecker was previously a portfolio Manager at Kinney Asset Management in Chicago and Arrow Investments. Mr. Selmo founded and managed portfolios for Eagle Lake Capital, LLC, and was an analyst at Third Avenue and Rothschild, Inc. They’re supported by six, soon to be seven analysts, a group that he calls “a tremendously strong team.”

-

Managing a closed fund is not as straightforward as it might appear. Funds are in a constant state of redemption, even if it’s not net Investors regularly want some of their money back to meet life’s other needs or to pursue other opportunities. When a fund is successful and open to new investors, those redemptions can be met – in whole or in large part – from new cash coming in. When a fund is closed, redemptions are met either from a fund’s cash reserves (or, more rarely, a secured line of credit) or from selective liquidation of securities in the portfolio. In bad times, the latter is almost always needed and plays havoc with both tax efficiency and portfolio positioning.

So, on whole, he argues that Crescent is quite manageable at its current size. While many fund managers have chosen to partially close their funds to manage inflows, Mr. Romick’s strategy is simply not to market it and allow any growth to be organic. That is, if investors show up, then fine, they show up. FPA has only two full-time marketers on payroll supporting six open-end mutual funds. While Romick speaks a lot to existing shareholders, his main outreach to potential shareholders is limited to stuff like speaking at the Morningstar conference.

While he agreed that Crescent was holding a lot of cash, reflecting a dearth of compelling investment opportunities, he’s willing to take in more money and let the fund grow. In explaining this rationale, he reflected on the maxim, “Winter is coming,” a favorite line from his daughter’s favorite television show. “The problem,” he said, “is that they never tell you when winter is coming. Just that it is. That’s the way I feel about the bond market today.” He made a point that resonated with Edward Studzinski’s repeated warnings over the past year: liquidity has been drained from the corporate bond market, making it incredibly fragile in the face of a panic. In 2007, for example, the market-makers had almost $300 billion in cash to oil the workings of the bond market; today, thanks to Dodd-Frank, that’s dwindled to less than $30 billion even as the high-yield and distressed securities markets – the trades that would most require the intervention of the market-makers – have ballooned. Much more market, much less grease; that’s a bad combination.

On the question of dodging responsibility, Mr. Romick’s response is simple. “We didn’t try to duck. We just wrote a paragraph that didn’t effectively communicate our meaning.” They wrote:

At first glance, it appears that we’ve declined as much as the market — down 11.71% since May 2015’s market peak against the S&P 500’s 11.30% decline — but that’s looking at the market only through the lens of the S&P 500. However, roughly half of our equity holdings (totaling almost a third of the Fund’s equity exposure) are not included in the S&P 500 index. Our quest for value has increasingly taken us overseas and our portfolio is more global than it has been in the past. We therefore consider the MSCI ACWI a pertinent alternative benchmark.

My observation was that you didn’t “appear to decline” as much as the stock market; you in actual fact did decline by that much, and a bit more. Mr. Romick’s first reflection was to suggest substituting “additional” for “alternative” benchmark. As the conversation unfolded, he and Mr. Leggio seemed to move toward imagining a more substantial rewrite that better caught their meaning. I might suggest:

We declined as much as the S&P 500 – down 11.71% from the May 2015 market peak to year’s end, compared to the S&P’s 11.30% decline. That might seem especially surprising given our high cash levels which should buffer returns. One factor that especially weighed against us in the short term is the fund’s significant exposure to international securities. Those markets had suffered substantially; from the May market peak, the S&P500 dropped 11.3% but international stocks (measured by the Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund) declined 23.5%. We are continuing to find interesting opportunities overseas and may add the global MSCI ACWI index as an additional benchmark to help you judge our performance.

So where does that leave us? Three things seem indisputable:

-

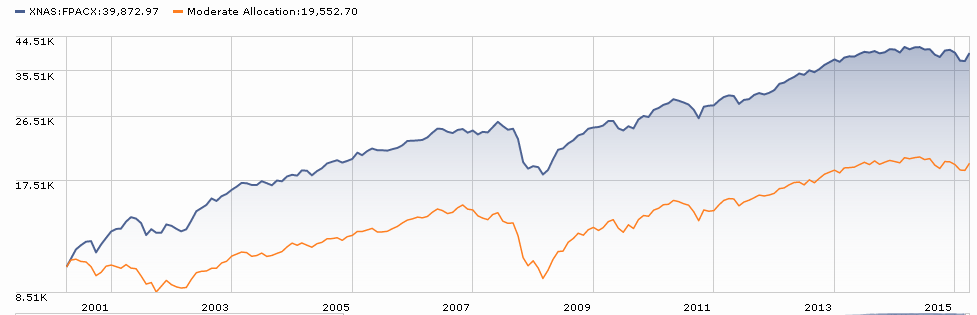

Crescent is still a large fund. As I write this (3/10/16), Morningstar reports that Crescent has $16.6 billion in assets, well down from its $20.5 billion 2015 peak. A year ago it was larger and still growing. Now, it’s both smaller and FPA expects “modest outflows” in the year ahead. This still makes it one of the hundred largest actively managed funds, the ninth largest “moderate allocation” fund (Morningstar) and the third-largest “flexible portfolio” fund (Lipper). The larger funds tend to be multi-manager beasts from huge complexes such as American Funds, BlackRock, Fidelity, Price and Vanguard.

On the upside, its equity positions have still managed to beat the S&P 500 in five of the past seven calendar years.

-

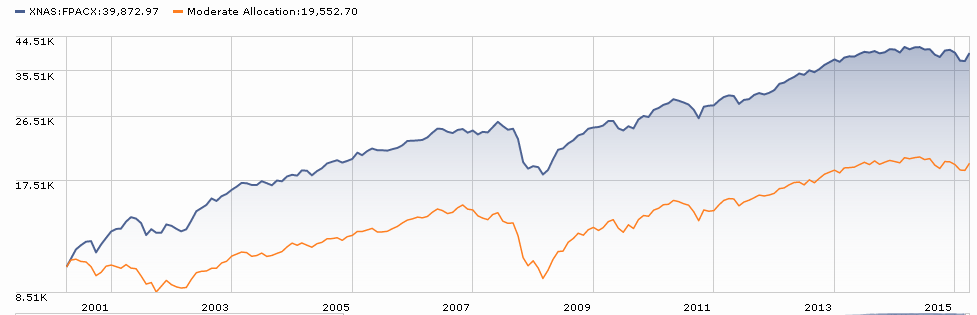

Crescent is led by a very talented manager. His recognition as Morningstar’s 2013 Asset Allocation Fund Manager of the Year is one of those “scratch the surface” sorts of statements. He’s beaten his Morningstar peers in eight of the past 10 years; the fund leads 99% of its peers over the past 15 years. Morningstar describes him as “one of the most accomplished” managers in the field and he routinely ends up on lists of stars, masters and gurus. He’s managed Crescent for just under a quarter century which creates a well-documented record of independence and success. While we have no independent record for his co-managers, we also have no reason to doubt their ability.

-

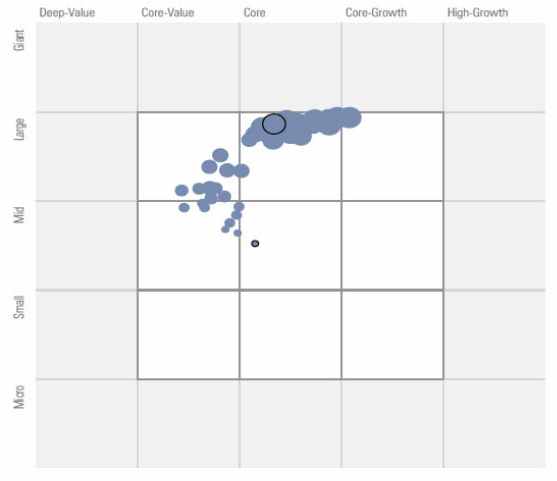

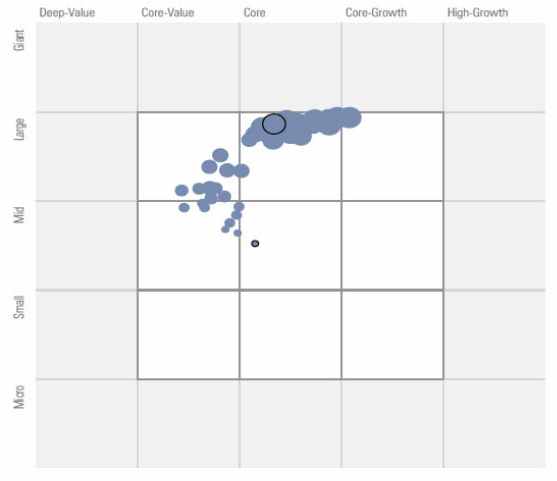

Crescent is not the fund it once was. It’s no longer a small fund driven by one guy’s ability to find and exploit opportunities in small and mid-cap stocks or other small issues. In the course of reflecting on the general failure of flexible funds, a rule to which Crescent is the exception, John Rekenthaler offered a graphic representation of the fund’s evolution over the past decade:

The size of the dot reflects the size of the fund. The position of the dot reflects the positioning of the stock portion of the portfolio. Tiny dot with the black circle was Crescent a decade ago; big dot with the black circle is today. Currently, 82% of the fund’s stocks are characterized by Morningstar as “large” or “giant,” with more giants than merely large caps. The average market cap is just north of $50 billion. According to Mr. Romick, these securities are more reflective of the opportunity set based on valuations, than a byproduct of the Fund’s size.

The unanswered question is whether the new Crescent remains a peer of the old Crescent. Over the past 15 years, Crescent has beaten 99% of its peers and it’s beaten them by a huge margin.

I don’t think the fund will be capable of reprising that dominance; conditions are too different with both the fund and the market. The question, I suppose, is whether that’s a fair standard? Likely not.

The better question is, can the fund consistently and honorably deliver on its promise to its investors; that is, to provide equity-like returns with less risk over reasonable time periods? Given that the management team is deeper, the investment process is unimpaired and its size is has become more modest, I think the answer is “yes.” Even if it can’t be “the old Crescent,” we can have some fair confidence that it’s going to be “the very good new Crescent.”

Share Classes

Last month, David Offered Without Comment: Your American Funds Share Class Options. The simple table showing 18 share classes offered for one of AF’s fixed income funds generated considerable comment via Twitter and other media, including good discussion on the MFO Discussion Board.

Last month, David Offered Without Comment: Your American Funds Share Class Options. The simple table showing 18 share classes offered for one of AF’s fixed income funds generated considerable comment via Twitter and other media, including good discussion on the MFO Discussion Board.

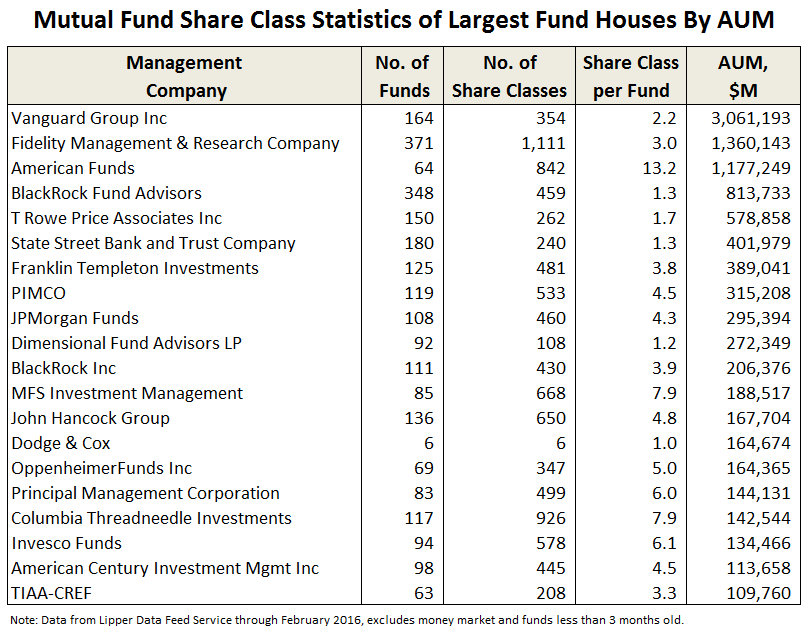

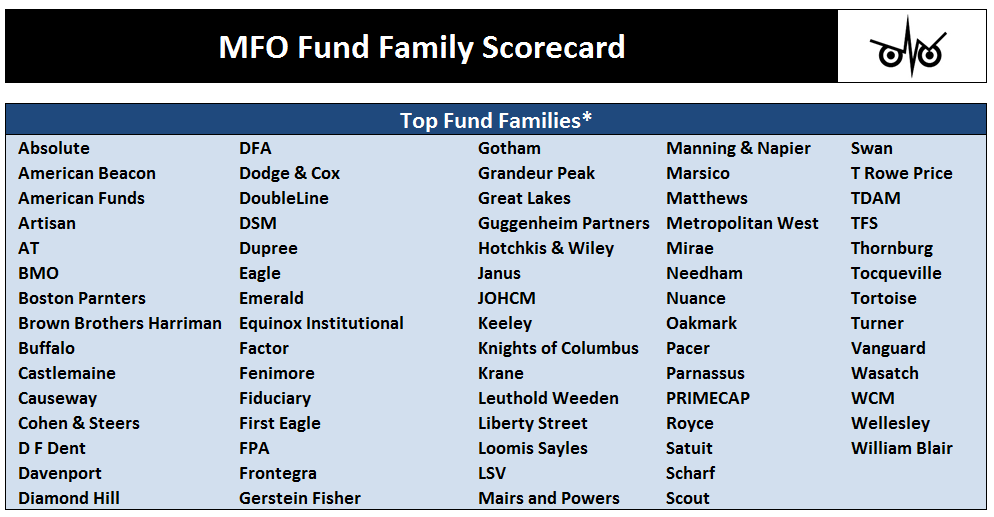

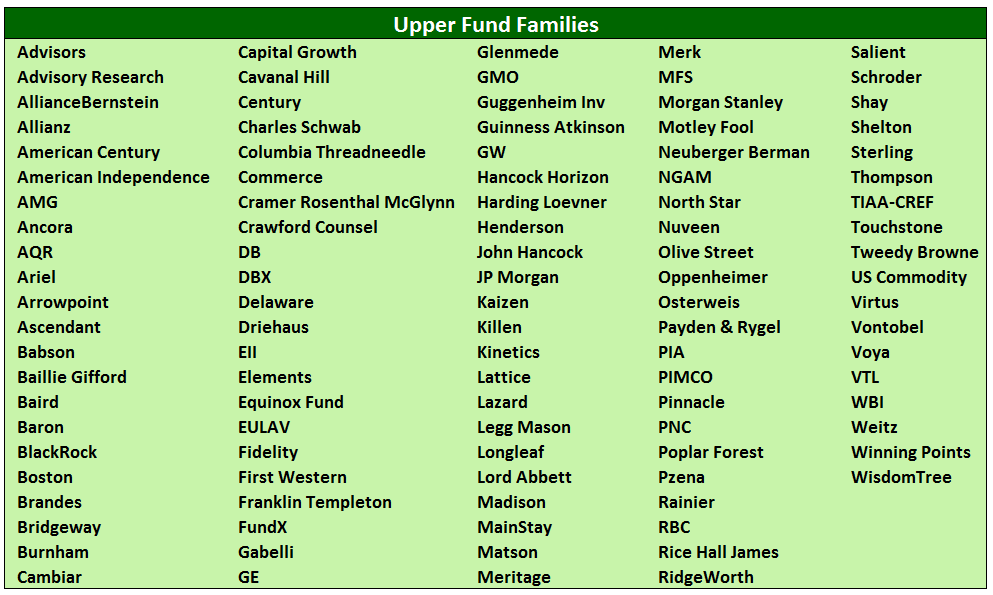

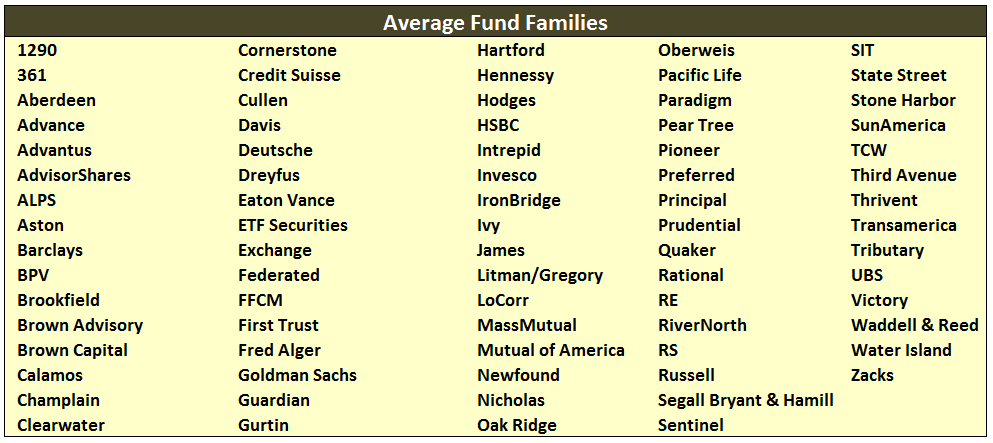

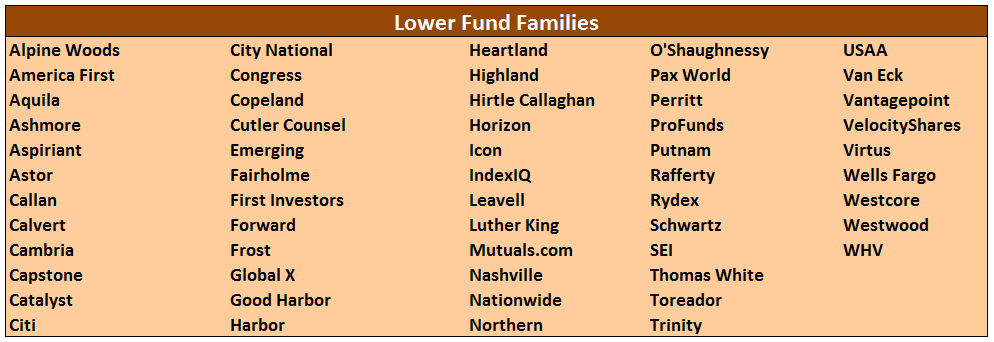

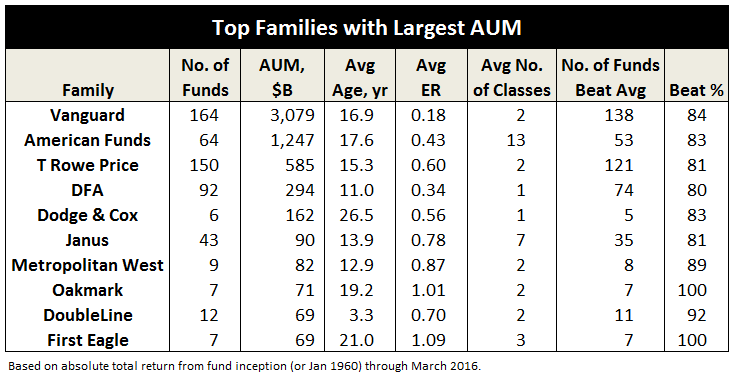

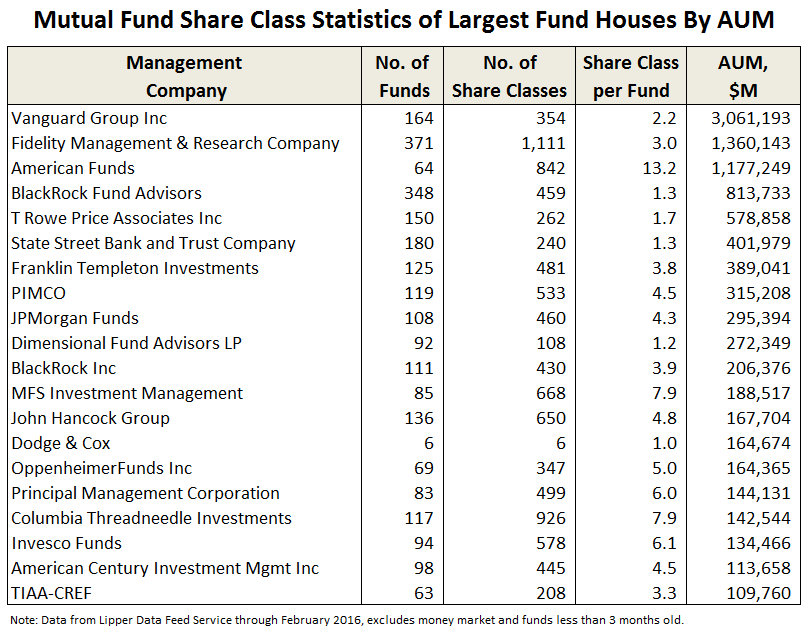

We first called attention to excessive share classes in June 2014 with How Good Is Your Fund Family? (A partial update was May 2015.) American Funds topped the list then and it remains on top today … by far. It averages more than 13 share classes per unique fund offering.

The following table summarizes share class stats for the largest 20 fund management companies by assets under management (AUM) … through February 2016, excluding money market and funds less than 3 months old.

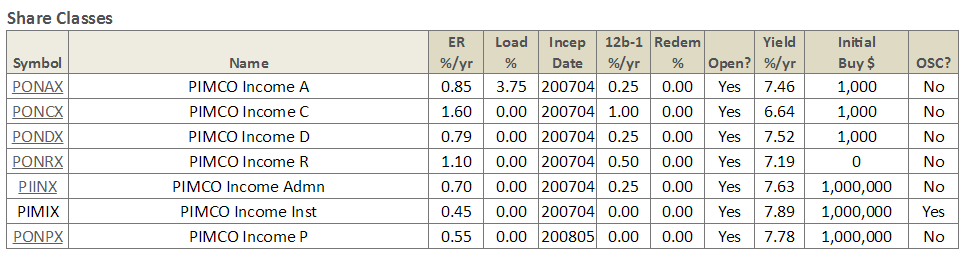

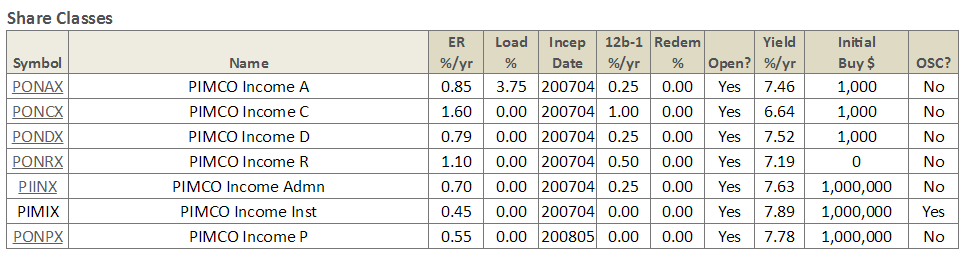

At the end of the day, share classes represent inequitable treatment of shareholders for investing in the same fund. Typically, different share classes reflect different expense ratios depending on initial investment amount, load or transaction fee, or association of some form, like certain 401K plans. Here’s a link to AF’s web page explaining Share Class Pricing Details. PIMCO’s site puts share class distinction front and center, as seen in its Products/Share Class navigator below, a bit like levels of airline frequent flyer programs:

We’ve recently added share class info to MFO Premium’s Risk Profile page. Here’s an example for Dan Ivascyn’s popular Income Fund (click on image to enlarge):

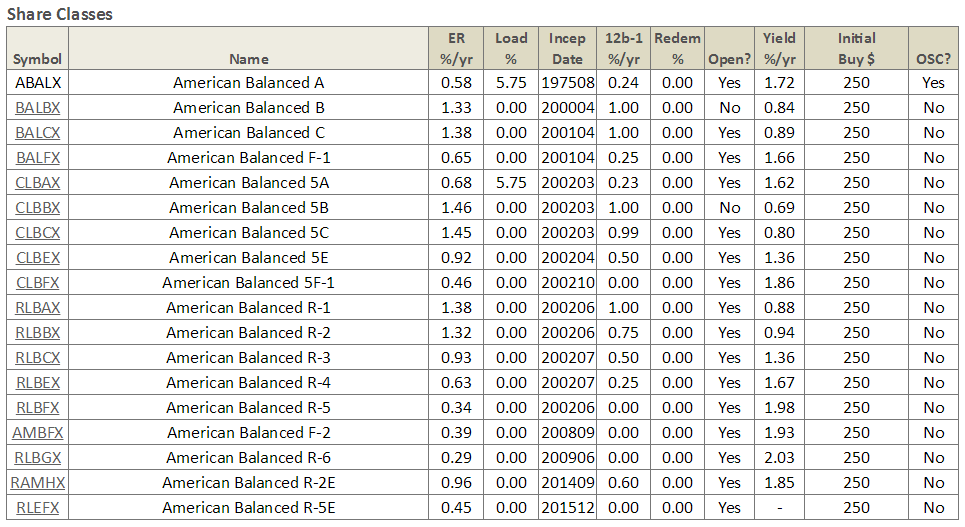

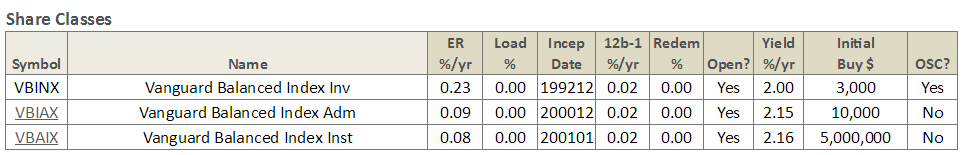

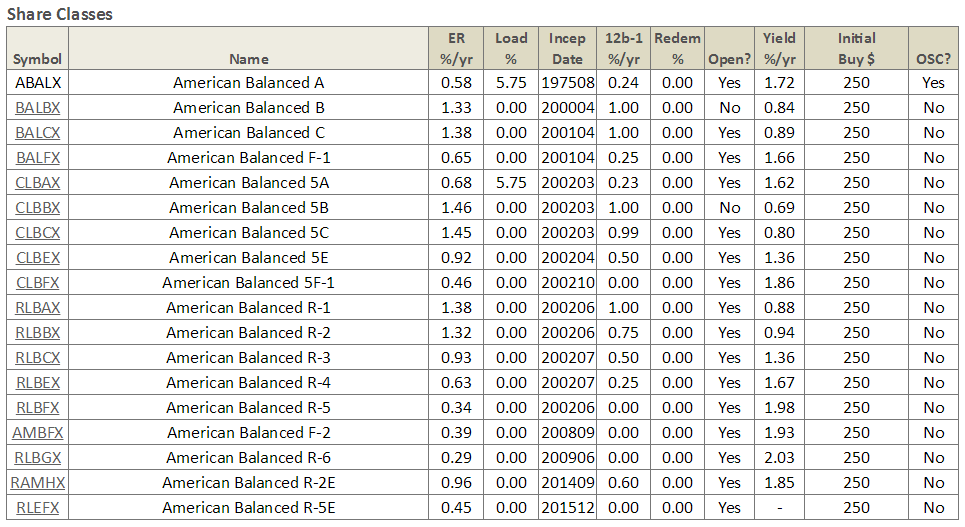

In addition to the various differences in 12b-1 fee, expense ratio (ER), maximum front load, and initial purchase amount, notice the difference in dividend yield. The higher ER of the no-load Class C shares, for example, comes with an attendant reduction in yield. And, another example, from AF, its balanced fund:

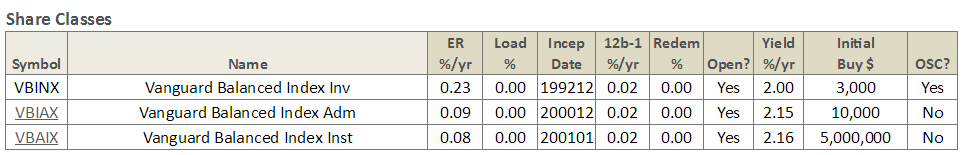

Even Vanguard, known for low fees and equitable share holder treatment, provides even lower fees to its larger investors, via so-called Admiral Shares, and institutional customers. Of course, the basic fees are so low at Vanguard that the “discount” may be viewed more as a gesture.

The one fund company in the top 20 that charges same expenses to all its investors, regardless of investment amount or association? Dodge & Cox Funds.

We will update the MFO Fund House Score Card in next month’s commentary, and it will be updated monthly on the MFO Premium site.

Shake Your Money Market

By Leigh Walzer

Reports of the death of the money market fund (“MMF”) are greatly exaggerated. Seven years of financial repression and 7-day yields you can only spot under a microscope have made surprisingly little dent in the popularity of MMF’s. According to data from the Investment Company Institute, MMF flows have been flat the past few years. The share of corporate short term assets deposited in MMFs has remained steady.

However, new regulations will be implemented this October, forcing MMFs holding anything other than government instruments to adopt a floating Net Asset Value. These restrictions will also allow fund managers to put up gates during periods of heavy outflows.

MMFs were foundational to the success of firms like Fidelity, but today they appear to be marginally profitable for most sponsors. Of note, Fidelity is taking advantage of the regulatory change to move client assets from less remunerative municipal MMFs to government money market funds carrying higher fees (management fees net of waived amounts.)

While MMFs offer liquidity and convenience, the looming changes may give investors and advisors an impetus to redeploy their assets. In a choppy market, are there safe places to park cash? A popular strategy over the past year has been high-dividend / low-volatility funds. We discussed this in March edition of MFO. This strategy has been in vogue recently but with a beta of 0.7 it still has significant exposure to market corrections.

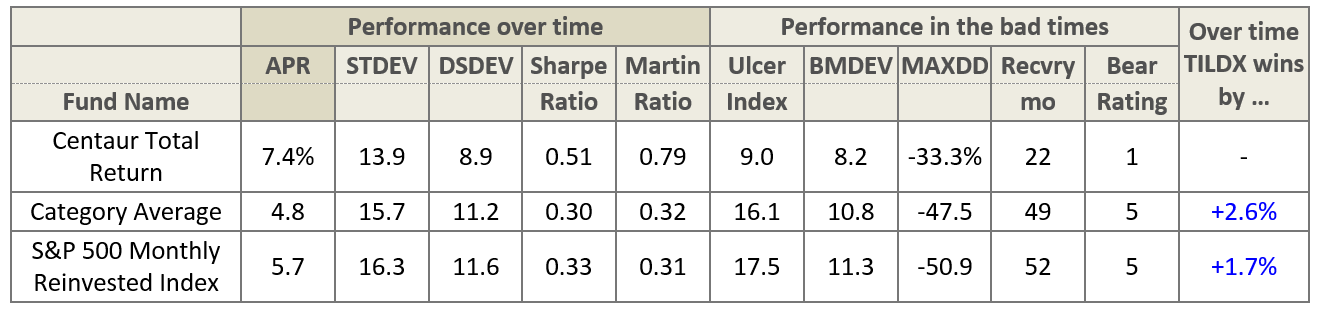

Short Duration Funds: Investors who wish to pocket some extra yield with a lower risk profile have a number of mutual fund and ETF options. This month we highlight fixed income portfolios with durations of 4.3 years or under.

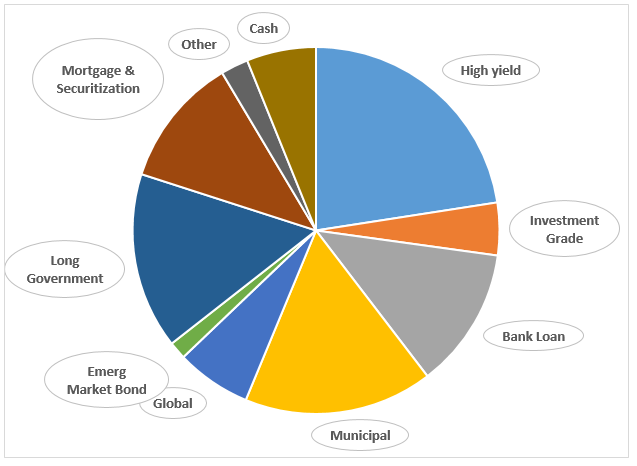

We count roughly 300 funds with short or ultraShort Duration from approximately 125 managers. Combined assets exceed 500 billion dollars. Approximately one quarter of those are tax-exempt. For investors willing to risk a little more duration, illiquidity, credit exposure, or global exposure there are roughly 1500 funds monitored by Trapezoid.

Duration is a measure of the effective average life of the portfolio. Estimates are computed by managers and reported either on Morningstar.com or on the manager’s website. There is some discretion in measuring duration, especially for instruments subject to prepayment. While duration is a useful way to segment the universe, it is not the only factor which determines a fund’s volatility.

Reallocating from a MMF to a Short Duration fund entails cost. Expenses average 49 basis points for Short Term funds compared with 13 basis points for the average MMF. Returns usually justify those added costs. But how should investors weigh the added risk. How should investors distinguish among strategies and track records? How helpful is diversification?

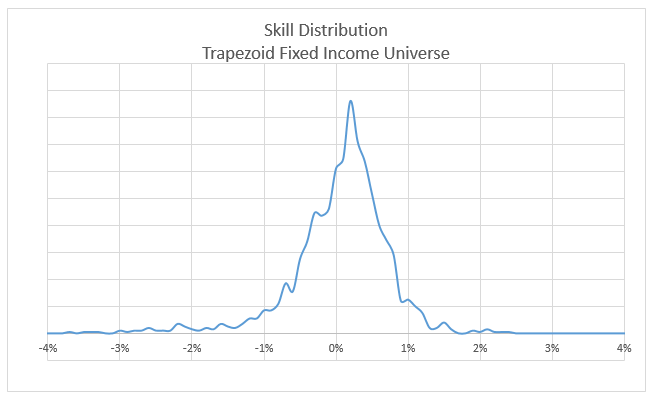

To answer these questions, we applied two computer models, one to measure skill and another to select an optimal portfolio.

We have discussed in these pages Trapezoid’s Orthogonal Attribution Engine which measures skill of actively managed equity portfolio managers. MFO readers can learn more and register for a demo at www.fundattribution.com. Our fixed income attribution model is a streamlined adaptation of that model and has some important differences. Among them, the model does not incorporate the forward looking probabilistic analysis of our equity model. Readers who want to learn more are invited to visit our methodology page. The fixed income model is relatively new and will evolve over time.

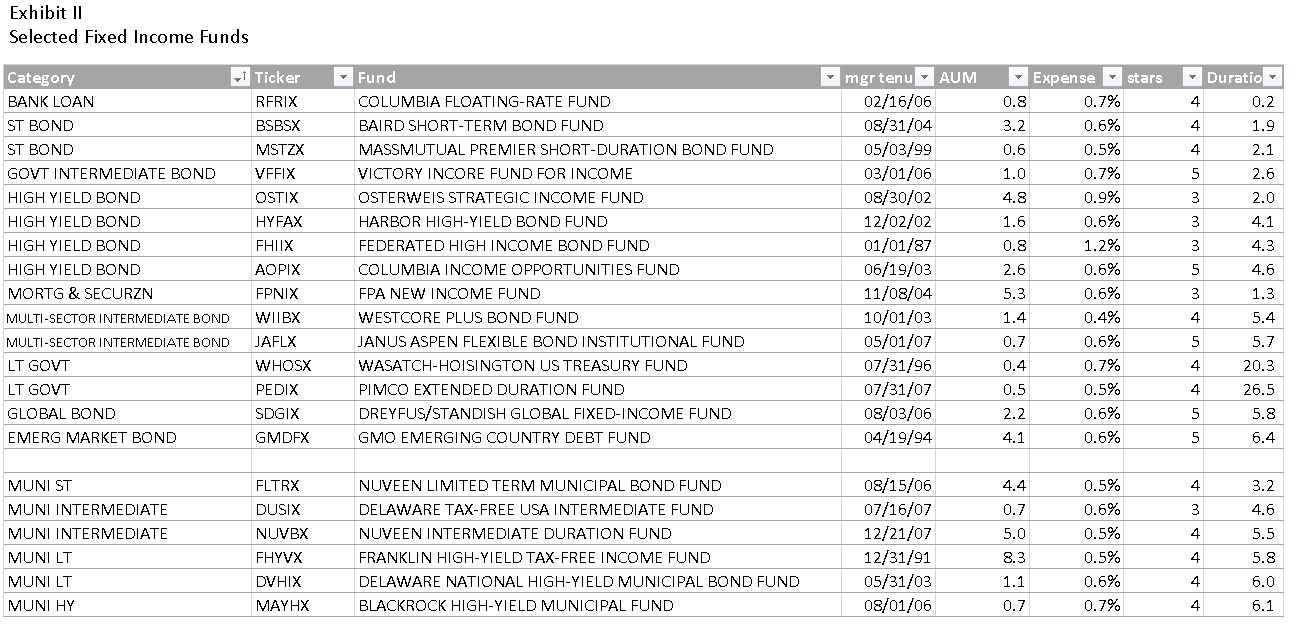

We narrowed the universe of 1500 funds to exclude not only unskilled managers but fund classes with AUM too small, duration too long, tenure too short (<3 years), or expenses too great (skill had to exceed expenses, adjusted for loads, by roughly 1%). We generally assumed investors could meet institutional thresholds and are not tax sensitive. For a variety of reasons, our model portfolio might not be right for every investor and should not be construed as investment advice.

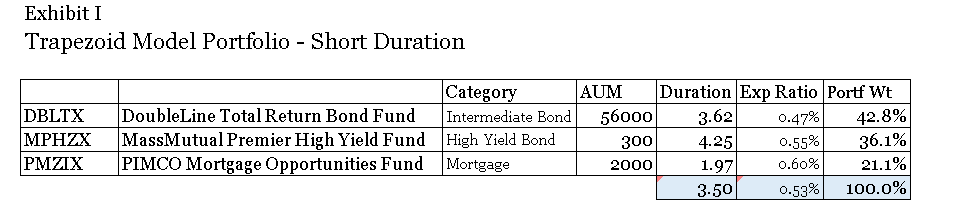

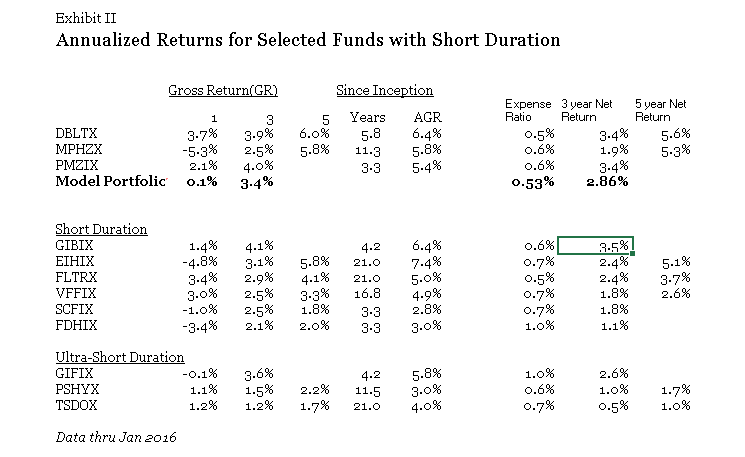

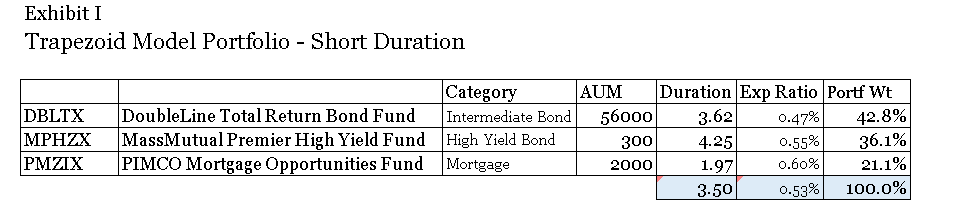

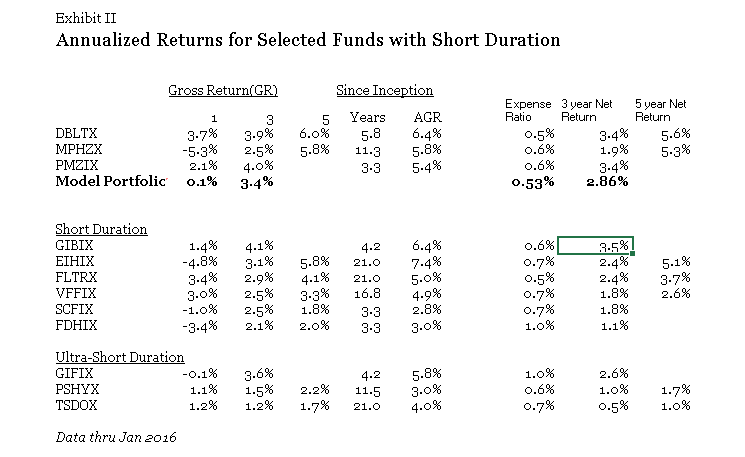

DoubleLine Total Return Bond (DBLTX), MassMutual Premier High Yield Fund (MPHZX), and PIMCO Mortgage Opportunities Fund (PMZIX) all receive full marks from Morningstar and Lipper (except in the area of tax efficiency.) Diversifying among credit classes and durations is a benefit – but the model suggests these three funds are all you need.

Honorable Mentions: The model finds Guggenheim Total Return Bond Fund (GIBIX) is a good substitute for DBLTX and Shenkman Short Duration High Income Fund (SCFIX) is a serviceable substitute for MPHZX. We ran some permutations in which other funds received allocations. These included: Victory INCORE Fund for Income (VFFIX), Nuveen Limited term Municipal Bond (FLTRX), First Trust Short Duration High Income Fund (FDHIX), Guggenheim Floating Rate Strategies (GIFIX), and Eaton Vance High Income Opportunities Fund (EIHIX).

The Trapezoid Model Portfolio generated positive returns over a 12 and 36-month time frame. (Our data runs through January 2016.) The PIMCO Mortgage fund wasn’t around 5 years ago, but it looks like the five-year yield would have been close to 6%.

The portfolio has an expense ratio of 53 basis points. Our algorithms reflect Trapezoid’s skeptical attitude to high cost managers. There are alternative funds in the same asset classes with expense ratios of 25 basis points of better. But superb performance more than justifies the added costs. Our analysis suggests the rationale for passive managers like Vanguard is much weaker in this space than in equities. However, investors in the retail classes may see higher expenses and loads which could change the analysis.

No Return Without Risk: How much risk are we taking to get this extra return? The duration of this portfolio is just under 3.5 years. There is some corporate credit risk: MPHZX sustained a loss in the twelve months ending January. It is mostly invested in BB and B rated corporate bonds. To do well the fund needs to keep credit loss under 3%/yr. Although energy exposure is light, we see dicey credits including Valeant, Citgo, and second lien term loans. The market rarely gives away big yields without attaching strings.

The duration of this portfolio hurt returns over the past year. What advice can we give to investors unable to take 3.5 years of duration risk? We haven’t yet run a model but we have a few suggestions.

- For investors who can tolerate corporate credit risk, Guggenheim Floating Rate Strategies (GIFIX) did very well over the past 5 years and weathered last year with only a slight loss.

- A former fixed income portfolio manager who now advises clients at Merrill Lynch champions Pioneer Short Term Income Fund (PSHYX). Five-year net return is only 2.2%, but the fund has a duration of only 0.7 years and steers clear of corporate credit risk.

- A broker at Fidelity suggested Touchstone UltraShort Duration Fixed Income Fund (TSDOX) which has reasonable fees and no load.

Short Duration funds took a hit during the subprime crisis. At the trough bond fund indices were down 7 to 10% from peak, depending on duration. Funds with concentrations in corporate credit and mortgage paper were down harder while funds like VFFIX which stuck to government or municipal bonds held up best. MassMutual High Yield was around during that period and fell 21% (before recovering over the next 9 months.) The other two funds were not yet incepted; judging from comparable funds the price decline during the crisis was in the mid-single digits. Our model portfolio is set up to earn 2.5% to 3% when rates and credit losses are stable. Considering that their alternative is to earn nothing, investors deploying cash in Short Duration funds appear well compensated, even weighing the risk of a once-in-a-generation 10% drawdown.

Bottom Line: The impact of new money market fund regulations is not clear. Investors with big cash holdings have good alternatives. Expenses matter but there is a strong rationale for selecting active managers with good records, even when costs are above average. Investors get paid to take risk but must understand their exposure and downside. A moderate amount of diversification among asset classes seems to be beneficial. Our model portfolio is a good starting point but should be tailored to the needs of particular investors.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

The stuff Leigh shares here reflects the richness of the analytics available on his site and through Trapezoid’s services. If you’re an independent RIA or an individual investor who need serious data to make serious decisions, Leigh offers something no one else comes close to. More complete information can be found at www.fundattribution.com. MFO readers can sign up for a free demo.

The Alt Perspective: Commentary and news from DailyAlts.

For anyone who enjoys roller coasters, Q1 2016 was for you. While it seemed a bit wild at times, it was really just a trip down to the bottom of a trough, and a consistent tick back up to where we started. Thanks to a coordinated plan of attack on part of global sovereign bankers, and reiterated by new policy actions from the European Central Bank, the markets shrugged off early losses in the year with a very solid recovery in March. As they say, don’t fight the Fed. And in this case, don’t fight the globally coordinated Fed.

For anyone who enjoys roller coasters, Q1 2016 was for you. While it seemed a bit wild at times, it was really just a trip down to the bottom of a trough, and a consistent tick back up to where we started. Thanks to a coordinated plan of attack on part of global sovereign bankers, and reiterated by new policy actions from the European Central Bank, the markets shrugged off early losses in the year with a very solid recovery in March. As they say, don’t fight the Fed. And in this case, don’t fight the globally coordinated Fed.

Let’s first take a look at how alternative funds faired in the bull month of March.

Performance

The returns for the month of March were positive, except for managed futures and bear market funds. Commodities led the way over the month, while bear market funds got hammered with the strong rally in equities. Managed futures struggled to add value as markets tended to be one directional in March.

Commodities Broad Basket 4.32%

Long/Short Equity 2.53%

Multicurrency 2.52%

Nontraditional Bond 1.65%

Multialternative 1.27%

Market Neutral 0.46%

Managed Futures -2.79%

Bear Market -10.86%

Cleary, equity based alternative strategies, such as long/short equity, struggled to keep up with the strong rally in March, however, nontraditional bond funds performed well relative to their long-only counterpart (Intermediate Term Bonds). Below are a few traditional mutual fund categories:

Large Blend (US Equity) 6.37%

Foreign Large Blend 6.86%

Intermediate Term Bond 1.30%

Moderate Allocation 4.72%

Data Source: Morningstar

Research

Two interesting pieces of research emerged over the month. The first is from an investment advisor in La Jolla, California, called AlphaCore Capital. In a piece written by their director of research, they highlight the importance of research and due diligence when choosing alternative investment managers (or funds) – not because the strategies are more complex (which is also a reason), but because the range of returns for funds in each category is so wide. This is called “dispersion,” and it is a result of the investment strategies and the resulting returns of funds in the same category being so different. Understanding these differences is where the expertise is needed.

The second piece of research comes from Goldman Sachs. In their new research report, they note that liquid alternatives outperformed the pricier hedge funds across all five of the major categories of funds they track. While the comparative results in some categories were close, the two categories that stood out with significant differences were Relative Value and Event Driven. In both cases, alternative mutual funds outperformed their hedge fund counterparts by a wide margin.

Fund Liquidations

Nineteen alternative mutual funds were liquidated over the quarter, with seven of those in March. Most notably, Aberdeen (the new owner of the fund-of-hedge fund firm Arden Asset Management) closed down the larger of the two Arden multi-alternative funds, the Arden Alternative Strategies Fund (ARDNX). The fund had reached a peak of $1.2 billion in assets back in November 2014, but lackluster performance in 2015 put the fund on the chopping block.

In addition to the Arden fund, Gottex Fund Management (another institutional fund-of-hedge funds, as is Arden) liquidated their only alternative mutual fund, the Gottex Endowment Strategy Fund (GTEAX), after losing nearly 6% in 2015. Both of these closures create concerns about the staying power and commitment by institutional alternative asset management firms. And both come on the back of other similar firms, such as Collins Capital and Whitebox (the latter being a hedge fund manager), who both liquidated funds in February.

Where to from here?

Challenging performance periods always serve to clean out the underperformers. In many ways, Q1 served as a housecleaning quarter whereby funds that wrapped up 2015 with few assets and/or below average (or well-below average) performance took the opportunity to shut things down. A little housecleaning is always good. Looking forward, there is significant opportunity for managers with strong track records, compelling diversification, and consistent management teams.

Alternative investment strategies, and alternative asset classes, both have a role to play in a well-diversified portfolio. That fact hasn’t changed, and as more financial advisors and individual investors grow accustom to how these strategies and asset classes behave, the greater the uptake will be in their portfolios.

Be well, stay diversified and do your due diligence.

Observer Fund Profiles:

Each month the Observer provides in-depth profiles of between two and four funds. Our “Most Intriguing New Funds” are funds launched within the past couple years that most frequently feature experienced managers leading innovative newer funds. “Stars in the Shadows” are older funds that have attracted far less attention than they deserve.

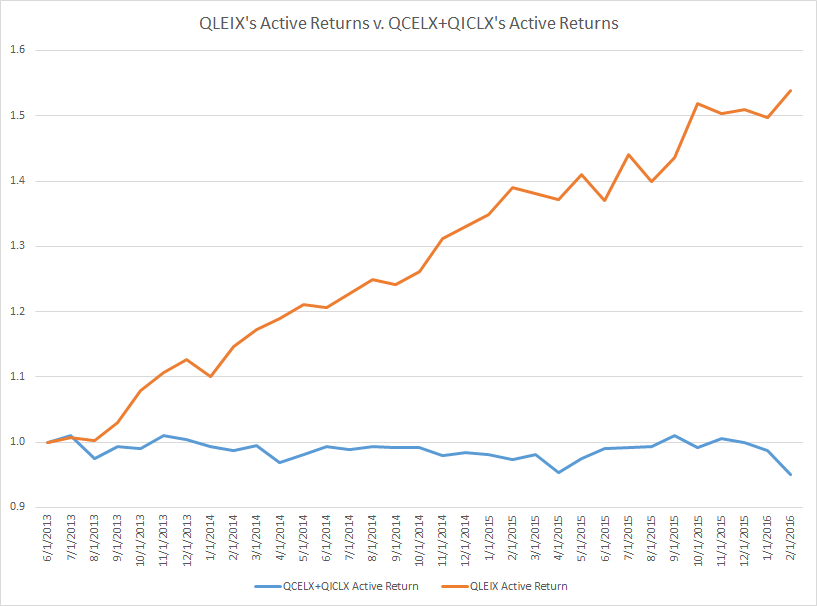

AQR Equity Market Neutral (QMNIX) and AQR Long-Short Equity (QLEIX): our colleague Sam Lee, principal of Severian Asset Management, offers a close assessment of two institutional AQR funds. The bottom line is: “AQR does long-short investing right. Check these out.”

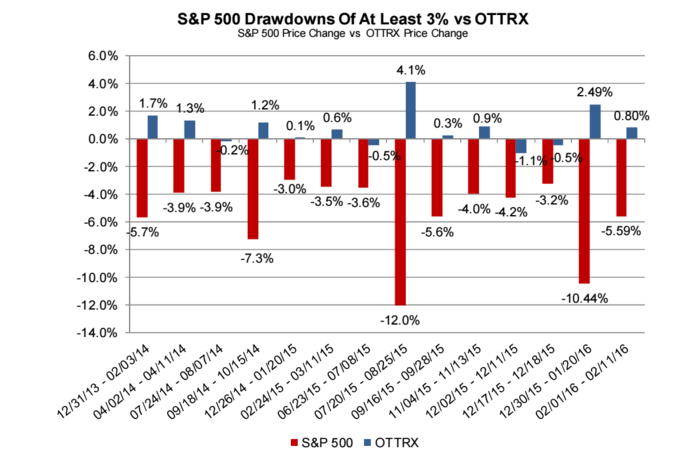

Intrepid Endurance (ICMAX): at 70% cash, what’s to like? Well, the highest Sharpe ratio of any small cap fund – domestic, global, or international – of the course of the full market cycle. Also the lower Ulcer Index. And peer-beating returns. Heck, what’s not to like?

Otter Creek Long/Short Opportunity (OTCRX): we’d describe the young Otter Creek fund as “pure alpha” – it has outperformed its peers by 11% a year since inception – except that it’s also done it was lower volatility and a near-zero correlation to the market. We’ll leave it to you to sort out.

Funds in Registration

Whether it’s the time of year or the sense of an industry-wide death spiral, the number of new funds in registration has been steadily declining. This month saw either six or 20 filings, depending on how you could a weird series of options funds from a group called Vest Financial. Two funds start out:

Moerus Worldwide Value Fund marks the return of Amit Wadhwaney, who managed Third Avenue International Value (TAVIX) from 2001-2013. Morningstar described Mr. Wadhwaney as “skilled and thoughtful.” His fund was distinguished by somewhat better than average returns with “markedly lower” volatility and strong down-market performance. The fund’s performance since his departure has been disastrous.

Sit ESG Growth Fund which targets financially sound firms with good ESG records. The success of the other funds in the Sit family suggests that values-driven investors might find it worth investigating.

Manager Changes

We’ve track down rather more than 70 manager changes this month plus, of course, the one MANAGER CHANGE! Which is to say, Mr. Goldfarb’s departure from Sequoia.

Updates

Congratulations to the good folks at Seafarer. Seafarer Overseas Growth & Income (SFGIX), topped $1.1 billion in assets in March, a singular achievement. In just over four years of operation, the fund has returned 24.8% while its average peer has lost 9.75%. Seafarer seems to have SEC clearance to launch their Seafarer Overseas Value fund, but has not yet done so.

Briefly Noted . . .

GlobalX and Janus are locked in a struggle to see who can release the greatest number of pointless ETFs in a month. The Global X entries are Health & Wellness Thematic ETF (BFIT), Longevity Thematic ETF (LNGR) and Millennials Thematic ETF (MILN). The latter focuses, like a laser, on those uniquely Millennial passions: “social and entertainment, clothing and apparel, travel and mobility, food/restaurants and consumer staples, financial services and investments, housing and home goods, education and employment, and health and fitness.” Janus weighed in with The Health and Fitness ETF, The Long Term Care ETF, The Obesity ETF and The Organics ETF. None have symbols but all will be available on May 31.

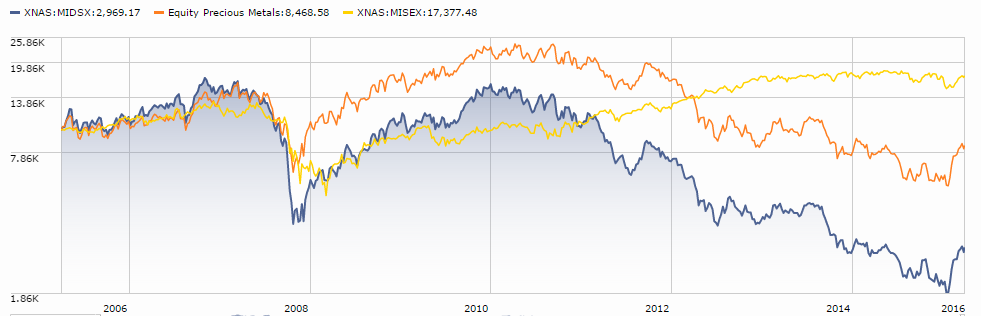

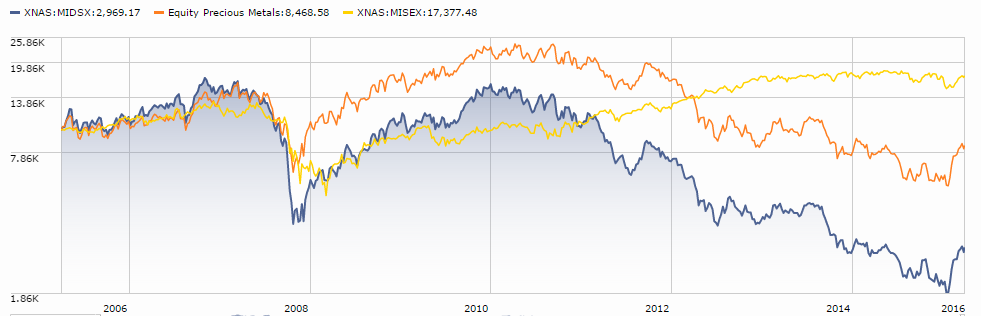

Upon further consideration of tax and other stuff, the Board of Trustees of Midas Series Trust has determined not to proceed with the merger of Midas Magic (MISEX) into the Midas Fund (MIDSX). This was an almost incalculably stupid plan from the get-go. MISEX is a diversified domestic equity fund whose top holdings include Berkshire-Hathaway, Google and Johnson & Johnson. Midas invests in gold miners. Over the last decade, Magic shares are up 74% while Midas lost 70%. And no, that’s not just because gold was down over the period; from 2006-2015, the spot price of gold rose from around $560 to about $1060. Here would be your investment options: Midas in blue, the average gold fund in, well, gold or Magic in yellow.

It’s easy to see why liquidating both funds makes sense. They’ve got $12-14 million in assets, weak to horrible long-term records and expenses pushing 4.0%. It’s hard to see how the Trustees managed to declare that “it’s in the best interest of the shareholders” to place them in Midas.

Effective March 31, 2016, the Templeton Foreign (TEMFX), Global Opportunities (TEGOZ) and World (TEMWX) funds gained the flexibility to “to hedge (protect) against currency risks using certain derivative instruments including currency and cross currency forwards and currency futures contracts.”

Tobin Smith, a financial tout for Fox News from 2000-2013, was nailed by the SEC for nearly $258,000 on charges that he fraudulently promoted a penny stock, IceWEB, to investors. Apparently the firm’s CEO wanted to pump its trading volume and price and, for a price, Mr. Smith and his firm was happy to oblige. The IceWEB scam occurred in 2012. He was terminated in 2013 over the on-air promotion of yet another stock.

SMALL WINS FOR INVESTORS

As of April 11, 2016, AllianzGI Ultra Micro Cap Fund (GUCAX) will reopen.

Effective April 1, 2016, the Boston Trust Small Cap Fund (BOSOX) and the Walden Small Cap Innovations Fund (WASOX) will no longer be closed to new investors.

The Gotham Index Plus Fund (GINDX) is reducing their administrative fee by 2 basis points, from 1.17% to 1.15%. Woo hoo! Including the “acquired fund fees and expenses,” the fund continues to cost institutional investors 3.28% per year. The reduction came on the $15 million fund’s first anniversary. The fund posted returns in the top 2% of its large-core peer group.

Invesco International Growth Fund (AIIEX) reopened to all investors on March 18, 2016. Class B shares are closed and will not re-open.

J.P. Morgan U.S. Large Cap Core Plus Fund (JLCAX) has reopened to new investors

Effective April 1, 2016, Kaizen Advisory, LLC (the “Advisor”) has lowered its annual advisory fee on Kaizen Hedged Premium Spreads Fund (KZSAX) from 1.45% to 1.10% and agreed to reduce the limit on total annual fund operating expenses by 0.35% to 1.75% for “A” shares.

CLOSINGS (and related inconveniences)

Effective April 30, 2016, the Diamond Hill Small-Mid Cap Fund (DHSCX) will close to most new investors.

On the general topic of “related inconveniences,” several fund advisors have decided that they need more of your money. The shareholders of LoCorr Managed Futures Strategy Fund (LFMAX) agreed, and voted to raise their fees management fees to 1.85%. To be clear: that’s not the fund’s expense ratio, that’s just the part of the fee that goes to pay the managers for their services. Similarly, shareholders at Monte Chesapeake Macro Strategies Fund (MHBAX) have voted to bump their managers’ comp to 1.70% of assets. In each case, the explanation is that the advisor needs the more to hire more sub-advisers.

OLD WINE, NEW BOTTLES

On May 2, American Century Strategic Inflation Opportunities Fund (ADSIX) will be renamed the Multi-Asset Real Return Fund. The plan is to invest primarily in TIPs with “a portion” in commodities-related securities and REITs.

As of April 1, 2016, Cavanal Hill Balanced Fund became Cavanal Hill Active Core Fund (APBAX). The big accompanying change: The percentage of equity securities that the Fund normally invest in shall change from “between 40% and 75%” to “between 40% and 75%.” If you’re thinking to yourself, “but Dave, those are identical ranges,” I concur.

Effective April 18, 2016, Columbia Small Cap Core (LSMAX) will change its name to Columbia Disciplined Small Core Fund.

Liquidation of JPMorgan Asia Pacific Fund (JAPFX). The Board of Trustees of the JPMorgan Asia Pacific Fund has approved the liquidation and dissolution of the fund on or about April 29, 2016.

Matthews Asia Science and Technology (MATFX) has been rechristened as Matthews Asia Innovators Fund. They formerly were constrained to invest at least 80% of their assets in firms that “derive more than 50% of their revenues from the sale of products or services in science- and technology-related industries and services.” That threshold now drops to 25%.

Pear Tree PanAgora Dynamic Emerging Markets Fund has been renamed Pear Tree PanAgora Emerging Markets Fund (QFFOX). At the same time, expenses have been bumped up from 1.37% (per Morningstar) to 1.66% (in the amendment on file). Why, you ask? The old version of the fund “allocate[d] its assets between two proprietary strategies: an alpha modeling strategy and a risk-parity strategy.” The new version relies on “two proprietary risk-parity sub-strategies: an alternative beta risk-parity sub-strategy and a “smart beta” risk-parity sub-strategy.” So there’s your answer: beta costs more than alpha.

The PENN Capital High Yield Fund has changed its name to the PENN Capital Opportunistic High Yield Fund (PHYNX).

The managers of the Rainier High Yield Fund (RIMYX), Matthew Kennedy and James Hentges, have announced their intention to resign from Rainier Investment Management and join Angel Oak Capital Advisors. Subject to shareholder approval (baaaaaa!), the fund will follow them and become Angel Oak High Yield. Shareholders are slated to vote in mid-April.

Effective on or about May 1, 2016, the name of each Fund set forth below will be changed to correspond with the following table:

| Current Fund Name |

Fund Name Effective May 1, 2016 |

| Salient Risk Parity Fund |

Salient Adaptive Growth Fund |

| Salient MLP & Energy Infrastructure Fund II |

Salient MLP & Energy Infrastructure Fund |

| Salient Broadmark Tactical Plus Fund |

Salient Tactical Plus Fund |

The Board of Trustees of Franklin Templeton Global Trust recently approved a proposal to reposition the Templeton Hard Currency Fund (ICPHX) as a global currency fund named Templeton Global Currency Fund. That will involve changing the investment goal of the fund and modifying the fund’s principal investment strategies.

Seeing not advantage in value, Voya is making the fourth name change in two years to one of its funds. Effective May 1, we’ll be introduced to Voya Global Equity Fund (NAWGX) which has been Voya Global Value Advantage since May 23, 2014. For three weeks it has been called Voya International Value Equity (May 1 – 23, 2014). Prior to that, it was just International Value Equity. The prospectus will remove “value investing” as a risk factor.

Thirty days later, Voya Mid Cap Value Advantage Fund (AIMAX) becomes Voya Mid Cap Research Enhanced Index Fund. The expense ratio does not change as it moves from “active” to “enhanced index,” though both the strategy and management do.

OFF TO THE DUSTBIN OF HISTORY

Breithorn Long/Short Fund (BRHAX) has closed and will liquidate on April 8, 2016.

Crow Point Defined Risk Global Equity Income Fund (CGHAX) has closed and will liquidate on April 25, 2016.

The Board of Trustees of Dreyfus Opportunity Funds has approved the liquidation of Dreyfus Strategic Beta U.S. Equity Fund (DOUAX), effective on or about April 15, 2016

DoubleLine just liquidated the last of three equity funds launched in 2013: DoubleLine Equities Growth Fund (DDEGX), which put most of its puddle of assets in high-growth mid- and large cap stocks. Based on its performance chart, you could summarize its history as: “things went from bad to worse.”

Dunham Alternative Income Fund (DAALX) will be exterminated (!) on April 25, 2016. (See, ‘cause the ticker reads like “Daleks” and the Daleks’ catchphrase was not “Liquidate!”)

On August 26, 2016, Franklin Flex Cap Growth Fund (FKCGX) will be devoured. Franklin Growth Opportunities Fund (FGRAX) will burp, but look appropriately mournful for its vanished sibling.

Frost Natural Resources Fund (FNATX) liquidated on March 31, 2016. Old story: seemed like a good idea when oil was $140/barrel, not so much at $40. In consequence, the fund declined 36% from inception to close.

Hodges Equity Income Fund (HDPEX) merged into the Hodges Blue Chip Equity Income Fund (HDPBX) on March 31, 2016. At $13 million each, neither is economically viable, really. $26 million will be tough but the fund’s record is okay, so we’ll be hopeful for them.

The Board of Trustees of LKCM Funds, upon the recommendation of Luther King Capital Management Corporation, the investment adviser to each fund, has approved a Plan of Reorganization and Dissolution pursuant to which the LKCM Aquinas Small Cap Fund (AQBLX) and the LKCM Aquinas Growth Fund (AQEGX), would be reorganized into the LKCM Aquinas Value Fund (AQEIX).

The Board of Trustees of the MassMutual Premier Funds has approved a Plan of Liquidation and Termination pursuant to which it is expected that the MassMutual Barings Dynamic Allocation Fund (MLBAX) will be dissolved. Effective on or about June 29, 2016 (the “Termination Date”), shareholders of the various classes of shares of the fund will receive proceeds in proportion to the number of shares of such class held by each of them on the Termination Date.

Oberweis Asia Opportunities Fund (OBAOX), a series of The Oberweis Funds (the “Trust”), scheduled for April 22, 2016, you will be asked to vote upon an important change affecting your fund. The purpose of the special meeting is to allow you to vote on a reorganization of your fund into Oberweis China Opportunities Fund (OBCHX).

On March 21, the Board of RX Traditional Allocation Fund (FMSQX) decided to close and liquidate it. Ten days later it was gone.

Satuit Capital U.S. Small Cap Fund (SATSX) will be liquidating its portfolio, winding up its affairs, and will distribute its assets to fund shareholders as soon as is practicable, but in no event later than April 15, 2016.

SignalPoint Global Alpha Fund (SPGAX) will liquidate on April 29, 2016.

Toroso Newfound Tactical Allocation Fund was liquidated on March 30, 2016.

On March 17, 2016, the Virtus Board of Trustees voted to liquidate the Virtus Alternative Income Solution (VAIAX), Virtus Alternative Inflation Solution (VSAIX), and Virtus Alternative Total Solution (VATAX) funds. They’ll liquidate around April 29, 2016.

In Closing . . .

May’s a big month for us as we celebrate our fifth anniversary. When we launched, Chip reported that the average life expectancy for a site like ours is … oh, six weeks. Even I’m a bit stunned as we begin a sixth year.

It goes without saying that you make it possible but, heck, I thought I’d say it anyway. Thanks and thanks and thanks again to you all!

Each month about 24,000 people read the Observer but about 6,000 of them are reading it for the first time. For their benefit, I need to repeat the explanation for the “hey, if you’re not charging and there aren’t any ads, how do you stay in business?” question.

Here’s the answer: good question! There are two parts to the answer. First, the Observer reflects the passions of a bunch of folks who are working on your behalf because they want to help, not because they’re looking for money. And so all of us work for somewhere between nothing (Brian, Charles, Ed, Sam, Leigh – bless you all!) and next-to-nothing (Chip and me). That’s not sustainable in the long term but, for now, it’s what we got and it works. So, part one: low overhead.

Second, we’re voluntarily supported by our readers. Some folks make tax-deductible contributions now and then (Thanks, Gary, Edward, and Mr. West!), some contribute monthly through an automatic PayPal setup (waves to Deb and Greg!) and many more use of Amazon link. The Amazon story is simple: Amazon rebates to us and amount equal to about 7% of the value of any purchase you make using our Amazon Associates link. It’s invisible, seamless and costs you nothing. The easiest way is set it and forget it: bookmark our Amazon link or copy it and paste it into your web browser of choice as a homepage. After that, it’s all automatic. A few hundred readers used our link in March; if we could get everybody who reads us to use the system, it would make a dramatic difference.

In May we’re also hoping to provide new profiles of two old friends: Aston River Road Independent Value and Matthews Asian Growth & Income. And, with luck, we’ll have a couple other happy birthday surprises to share.

Until then, keep an eye out in case you spot a huge dome wandering by. If so, let me know since we seem to be missing one!

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity. The best performing asset class in this quarter has been – gold. Actually the best performing asset class has been the gold miners, with silver not too far behind. We have had gold with a mid-teen’s total return. And depending on which previous metals vehicle you have invested in, you may have seen as much as a 60%+ total return (looking at the germane Vanguard fund). Probably the second best area generically has been energy, but again, you had to choose your spots, and also distinguish between levered and unlevered investments, as well as proven reserves versus hopes and prayers.

The best performing asset class in this quarter has been – gold. Actually the best performing asset class has been the gold miners, with silver not too far behind. We have had gold with a mid-teen’s total return. And depending on which previous metals vehicle you have invested in, you may have seen as much as a 60%+ total return (looking at the germane Vanguard fund). Probably the second best area generically has been energy, but again, you had to choose your spots, and also distinguish between levered and unlevered investments, as well as proven reserves versus hopes and prayers.

Here’s the brief version of recent events:

Here’s the brief version of recent events:

“Advertising is the modern substitute for argument; its function is to make the worse appear the better.”

“Advertising is the modern substitute for argument; its function is to make the worse appear the better.”

Last month, David

Last month, David

For anyone who enjoys roller coasters, Q1 2016 was for you. While it seemed a bit wild at times, it was really just a trip down to the bottom of a trough, and a consistent tick back up to where we started. Thanks to a coordinated plan of attack on part of global sovereign bankers, and reiterated by new policy actions from the European Central Bank, the markets shrugged off early losses in the year with a very solid recovery in March. As they say, don’t fight the Fed. And in this case, don’t fight the globally coordinated Fed.

For anyone who enjoys roller coasters, Q1 2016 was for you. While it seemed a bit wild at times, it was really just a trip down to the bottom of a trough, and a consistent tick back up to where we started. Thanks to a coordinated plan of attack on part of global sovereign bankers, and reiterated by new policy actions from the European Central Bank, the markets shrugged off early losses in the year with a very solid recovery in March. As they say, don’t fight the Fed. And in this case, don’t fight the globally coordinated Fed.

Sam Lee and

Sam Lee and